How Can We Plan for the Future in California?

The state’s heat waves, blackouts, and fires—amid a pandemic—offer a warning of our fossil-fuel future.

When I moved to California five years ago, I planted a tree in my yard. It was a Red Baron peach, chosen for its showy, bright-pink blossoms and its ability to grow fruit with few cool nights. For the past nine centuries, Southern California has been perfect for this tree, with mild winters and mild summers.

I planted the Red Baron for the climate we once had. That climate is no more. My neighborhood has already warmed by more than 2 degrees Celsius since the preindustrial period—twice the global average. In my short time as a Californian, I’ve seen a years-long drought. I’ve evacuated my home as a wildfire closed in. I’ve lived through unprecedented heat waves.

Trees, like all living beings, need time and stability to grow. But these essentials are no longer available. And it’s not just my backyard trees that are threatened under a changing climate. Many people have been grieving from the news that we may have lost some of the most majestic coastal redwoods to these latest fires. These giants have stood for more than a thousand years.

For my generation, and the ones coming up behind us, the simple act of planting trees now requires a leap of faith. I worry about how long they will last before they are taken by drought or fire. And if we can’t plan for our trees’ future, how are we supposed to plan for our children’s?

Right now my friends across the state are staring down disaster after disaster, suffering through climate change in action while they struggle with the ongoing pandemic.

Last week, a heat wave baked the West. In Death Valley, a world record may have been set for the hottest temperature observed on Earth: 130 degrees Fahrenheit. From Phoenix, Arizona, to the Bay Area, people turned up their air-conditioning, straining California’s electricity infrastructure, because the state imports power from its neighbors. Demand outstripped supply, and the grid operator started rolling blackouts. The cause is climate change: It has made heat waves five times more likely to occur in the western United States.

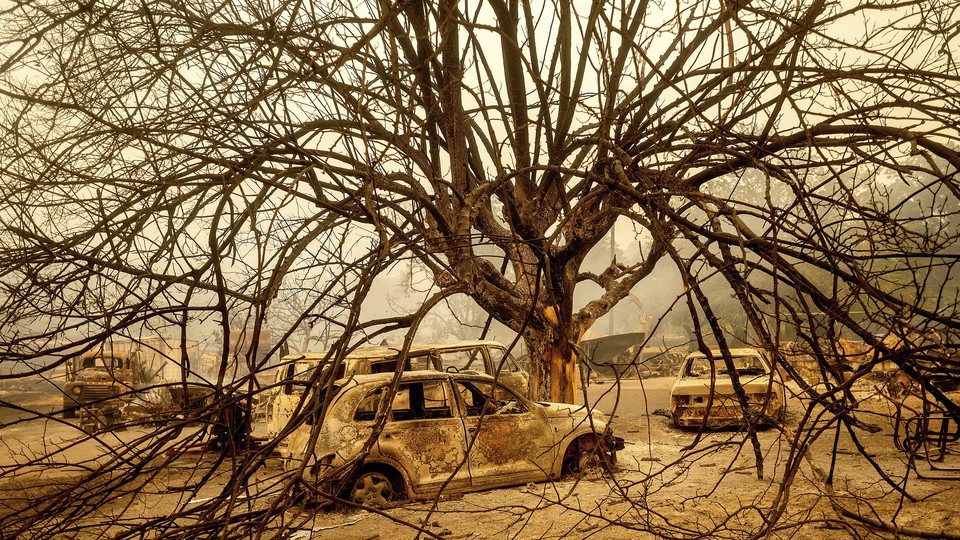

During the blackouts, California had unusually intense lightning strikes, which dotted the darkened landscape with electricity from the sky. These storms triggered fires across Northern California, forcing more than 100,000 people to evacuate their homes. Climate change has increased fire risk, and lengthened the fire season. It’s only August, and already more land has burned in California this year than all of 2019.

These climate disasters are happening against the backdrop of the still uncontrolled coronavirus outbreak, which makes it harder for people to flee to safety. Evacuating to a friend’s house or a community center when a highly contagious illness is circulating is not a simple choice.

Those theoretically “safe” in their homes don’t have it easy, either. Without electricity, many Californians have to choose between opening the windows and breathing in air choked with smoke, or keeping them closed in a hot house. My friend posted a picture of herself wearing an N95 mask with an exhalation valve, and a surgical mask on top: the first to protect herself against the smoke, the second to protect others from the virus.

I don’t want to live in a world where we have to decide which mask to wear for which disaster, but this is the world we are making. And we’ve only started to alter the climate. Imagine what it will be like when we’ve doubled or tripled the warming, as we are on track to do.

Climate change is not just destabilizing California’s grid. The East Coast is facing down a deadly hurricane season and has already seen outages for 1.4 million people. An unprecedented wind storm—which some are calling an “inland hurricane”—left a quarter million people in the Midwest without power.

Yet some people refuse to acknowledge that climate change is the cause of the problems California is facing. The Wall Street Journal published a misleading editorial blaming the state’s reliance on renewable energy for the outages.

In reality, several fossil-gas plants unexpectedly went offline when the heat wave struck, resulting in less available power. Gas plants can struggle to operate in the heat. In an ironic twist, burning fossil fuels will become less reliable in our hotter world. And California’s grid is connected to other states’, so when a heat wave spikes electricity demand from Arizona to Nevada, that leaves less power to import. With lower rainfall and many years of drought—again, caused in part by climate change—many of the state’s hydropower plants were also underperforming.

Simple human error also contributed to the blackouts. The agency in charge of operating the grid was confused about which plants were available to make electricity. One renewable-energy plant—a geothermal power station—was actually providing more power than the grid operator expected. The CEO of California’s grid operator put it simply: Renewables “are not a factor” in the blackouts.

My electric utility echoed this view in an email that urged people with solar power at home to help out. Despite electric utilities attacking rooftop-solar policy for the past decade, homes that produce extra power deliver excess energy to the grid, helping neighbors in need. More clean energy is a good thing.

California must continue on the path it has been on for years: leading the world in building the clean economy. In 1978, the state set its first goal for clean energy, aiming for 1 percent of power from wind energy. Forty years later, we now have a goal of 100 percent clean energy by 2045 in state law.

If anything, California must move faster. And we must get states from the Midwest to the South to do the same. The Biden campaign’s pledge to reach 100 percent clean power by 2035 exemplifies the kind of leadership we need in this time of crisis. Cleaning up our electricity system will allow us to eliminate about 80 percent of our carbon emissions, because we can use this clean power to fuel our cars, our homes, and some of our industries. Doing this will be a lot of work—so it will create millions of good-paying jobs that can’t be taken overseas.

We have seen what using fossil fuels has done to California. They have poisoned communities. Dirtied our air. And led to record fires, heat waves, and drought. We are not going back.

I still believe we can tackle the climate crisis. I’m still planting fruit trees in my backyard. At last count, I have 34—one for each year I’ve circled the sun. I don’t know how long they will stand, but I will keep doing everything I can to ensure their future.

What’s happening in California has a name: climate change. It doesn’t have to be this way. A better world is possible. For all of us, for all of our children, and even for our trees.