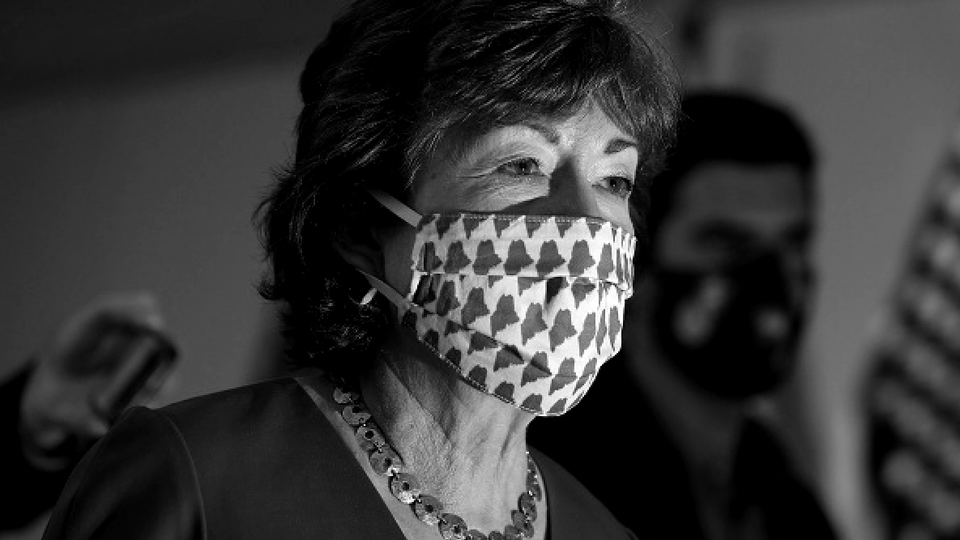

How Susan Collins Did It

The Republican’s surprising win in Maine represents a victory for moderation in a polarizing era.

KITTERY, Maine—When Senator Susan Collins bounded off her campaign bus here a week before the election, the obstacles to her reelection seemed insurmountable. The fourth-term Republican was facing an onslaught of Democratic cash, she hadn’t led a public poll in months, and voters in Maine were poised to deliver Donald Trump a resounding defeat.

To top it off, Collins was late to her own campaign.

Stuck in Washington lodging a futile protest against Amy Coney Barrett’s confirmation to the Supreme Court, Collins hadn’t stepped foot in her state in well over a week. She had raced north immediately after the final vote, desperate to make up the lost time. She flew into Boston and relaunched her bus tour in Kittery, the first town off I-95 after crossing the border from New Hampshire. A small smattering of supporters greeted Collins outside an 80-year-old trading post, where she gave short remarks and gamely answered questions from local reporters on topics she plainly didn’t want to talk about, including Barrett’s nomination and the man who had jammed it through the Senate over Collins’s objections, Mitch McConnell.

The political gods appeared to be conspiring against Collins, but this afternoon she pulled off a surprising victory. She easily defeated Democrat Sara Gideon in a race that gave Republicans a crucial upper hand in the battle for the Senate majority. In doing so, Collins retained the GOP’s last remaining congressional foothold in New England and signaled that, at least in a state like Maine, voters across the political spectrum would reward a centrist politician they trusted in a polarizing era.

Collins didn’t meet many voters upon her return to Maine; her events were COVID-friendly photo ops, not Trump-style rallies. But if the forces behind her win were a mystery, there were clues in the wide variety of voters who showed up. There were Trump loyalists and Trump haters, Republicans who backed Biden and even a former Hillary Clinton supporter who decided after the final presidential debate to vote for Trump. In Wells, the owner of a doughnut shop, Gary Leech, 63, presented Collins with cases of doughnut beer and refused her entreaties to pay for them. He told reporters that he’d be voting “to get rid of the nitwit” in the White House, but that he was a huge fan of Collins, even though he occasionally disagreed with her. “She’s a Republican with some class,” he said. “I just like the lady.”

Few Republicans struggled to navigate the Trump presidency as much, or as publicly, as Collins. Holding fast to her own brand of Republican moderation, she tried to straddle the center aisle but frequently found herself stretching too far to reach either side. Collins voted for the president’s tax bill but against his bid to repeal the Affordable Care Act, and against his impeachment. She supported his nominations of Brett Kavanaugh and Neil Gorsuch to the Supreme Court, but she voted against the confirmation of Barrett just days before the election. It was never enough—not for the Trump allies who wanted her to back the president more strongly, nor for his opponents who mocked her expressions of “concern” and “disappointment” whenever Trump crossed the line. By the time October rolled around, Collins’s bid to hug the middle had become something of a farce: In interviews and at televised debates, she steadfastly refused to say whether she’d even be voting for the president this fall.

At the heart of the race was a question: Had Collins changed, or had the voters of Maine, and the nature of politics more broadly? In her advertising, Gideon charged that Collins had, but when I asked the Democrat directly, she took the opposite view. “I actually don’t think Senator Collins has changed very much,” Gideon, the speaker of the Maine House, told me. “But I recognize that for many voters, that is the sentiment. My analysis is that the world around Senator Collins has changed.”

Collins ran on her independence, and her seniority. She reminded Mainers that she had delivered billions of dollars to the sparsely populated state over the years, and that if the voters sent her back to the Senate, she could chair the Appropriations Committee, and deliver untold billions more. She relied on that localized argument to counter the well-funded, nationalized pitch Gideon was making—that Collins had sided too often with Trump, and that a vote for her was also a vote for McConnell and Republican control of the Senate.

Powering Gideon’s campaign was a $70 million war chest—more than three times what Collins raised—and tens of millions more in outside cash. On the day I caught up with Collins, she had just learned that a national Democratic group backed by Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer had reserved another $4 million for the final week of the campaign, an amount equal to nearly $4 for every citizen of Maine. “That is unheard-of,” Collins said. “That is more than I spent on television in my entire race six years ago.”

To many of the voters I spoke with who had become disillusioned with Collins, it wasn’t that she had changed, exactly. They had assumed that she shared their sensibilities, that she would see the president as they saw him—as a threat to democratic norms, manifestly unfit to hold the office—and act accordingly. And now they realized that maybe they had been wrong. “She hasn’t stood up to Trump the way her bipartisanship should have led her to,” Clark Sulloway, a 27-year-old engineer from Lewiston, told me. “I just think Trump has disgraced America,” said Cindy DuBois, 55, a former Collins supporter.

If former Senator Jeff Flake of Arizona and Maine’s own William Cohen—whom Collins succeeded in the Senate—could denounce Trump so forcefully, why couldn’t a sensible, supposedly moderate Republican like Collins? Both men argued that Trump’s destructive character outweighed whatever positive conservative policies he might achieve. But Collins largely dodged those debates, instead emphasizing to voters that she would work with Trump when she agreed with him (on trade with China, for example, and on tax cuts) and oppose him when she didn’t (repeal of the Affordable Care Act). But the bigger difference between Cohen and Collins is that one is a former senator, and the other is a current one. Having lost the support of so many Democrats, Collins needed Trump’s base to win.

That challenge was evident when the president stopped briefly in Levant during a preelection campaign swing. Collins was stuck in Washington, but she probably wouldn’t have been invited anyway. At Treworgy Family Orchards, voter after voter proclaimed their unyielding support for Trump while saying they would much more reluctantly back Collins as well. They wished that she backed the president more strongly, and they lamented her support for abortion rights. In the end, Collins won even more votes in Levant than Trump did.

No vote dogged Collins as much as her decisive support for Kavanaugh, despite allegations that he’d sexually assaulted a woman at a high-school party. Publicly, Collins seemed to agonize about the choice, and waited until the day of the vote to announce her decision. Shortly before the climactic roll call, however, she delivered a 45-minute speech on the Senate floor planting herself firmly in Kavanaugh’s corner, defending his character and “centrist” jurisprudence while castigating the “special-interest groups” who had opposed him so fervently.

Democrats immediately targeted Collins for defeat this year, raising millions for an eventual opponent long before Gideon even entered the race. At Gideon’s events in the final weeks of the campaign, former Collins supporters invariably cited the Kavanaugh vote as a key factor in their decision to abandon her. She had lost even those who had known her for years—people like Marlene Viger, a retired nurse I met along with her niece, Debra Blais, at a “Supper With Sara” event in Rumford. Viger, a political independent, knows and likes Collins, and not just in the vague, impersonal way that a voter knows and trusts a politician she has long supported.

For years, the two women sat in adjacent seats at the University of Maine’s basketball games, cheering on the Black Bears and making small talk. Viger had voted for Collins every time she was on the ballot, until this year. “The Kavanaugh vote really turned us away,” Viger told me at a Gideon campaign event in October. Her voice was tinged not with anger or disgust, but with disappointment. “I actually feel sorry for her, because I know she has a difficult job and position,” she said. “It’s really sad.” As for Collins’s opposition to Barrett, she said it couldn’t make up for her Kavanaugh vote, or for the other times she hadn’t fought Trump hard enough. “It’s too late,” Viger said. “It’s an afterthought.”

Yet if there were plenty of voters who couldn’t forgive Collins for her Kavanaugh vote, there were others who did. One of them was Karen Boucher, a 46-year-old schoolteacher and political independent who cast an early ballot in Auburn, a town that narrowly went for Trump in 2016. She quickly told me she had voted for Biden, but when I asked whom she supported for Senate, she was almost apologetic: “This is going to sound awful, but I actually voted for Susan Collins.” After Collins’s vote for Kavanaugh, Boucher assumed that she would be supporting her opponent this year. She went back and forth several times, she said, but ultimately she returned to Collins based on her experience and because she was turned off by Gideon’s negative attacks. “I don’t agree with her choices, but she has tenure,” Boucher said.

The tallies across the state suggest that there were more voters like Karen Boucher than the polls favoring Gideon had indicated. Unlike Republican incumbents in Iowa and North Carolina, who benefited from a stronger-than-expected showing by Trump, Collins won a state that swung heavily away from the president; Maine gave Biden a double-digit win after going for Clinton by just three points in 2016. In Wells, a small coastal town in the state’s liberal southeast corner, Biden won by 15 points, while Collins won by nine.

Collins had amassed a similar coalition back in 2008, when she and Barack Obama each carried about 60 percent of the Maine vote. But the state’s politics, like the nation’s, have shifted. Wedged into the northeast corner of the country, Maine long seemed like a buffer against national political trends. As polarization increased through the 1990s and into the 2000s, Maine elected and reelected Collins and Senator Olympia Snowe, a duo who earned a reputation as two of the least partisan members of the Senate. Independent and third-party candidates are often major factors in the state’s elections, and when Snowe retired in 2012, voters chose an independent former governor, Angus King, who decided to caucus with the Democrats only after his victory.

In 2010, however, a narrow plurality of Mainers elected as governor Paul LePage, a conservative whose pugilist bluster would presage Trump’s. He won reelection in 2014, and two years later, the state’s split in the presidential election mirrored the nation’s. Hillary Clinton won the state by just 3 percent, on the strength of Maine’s more populated areas on the southeastern coast, including Portland. But the state’s sprawling, rural Second Congressional District flipped strongly to Trump after twice awarding its electoral vote to Obama.

The shift in the state was not lost on Collins. When she arrived in Washington in 1997, 19 Republicans represented New England in the House and Senate. By 2019, she was the only one left. “We’re living in polarized times, and Maine is not immune to that,” she told me. “The state used to be more moderate, more centrist in its political views. But my job is to represent all the people of Maine.”

Maine moved left again in 2018, as voters replaced the term-limited LePage with the Democrat Janet Mills and ousted GOP Representative Bruce Poliquin in favor of the Democrat Jared Golden in the Second District. Just as significant, voters also approved a new ranked-choice voting system that Democrats had pushed partly in response to LePage’s two elections, during which he never secured a majority of the electorate. The system works as an instant runoff, allocating second-choice votes if no candidate earns more than 50 percent. Ranked-choice voting helped put Golden over the top, and both the Collins and Gideon campaigns suspected that it would help the Democrat again this year. But Collins won a narrow but clear majority on the first ballot, negating the need for a ranked-choice tally.

She’ll return to a narrowly divided Senate potentially more powerful than ever, especially if Biden takes the White House while Republicans hold the majority. Collins will carry a rare mandate for moderation in her party, holding both the congressional GOP’s last remaining vote in New England and one of the last true swing votes in Washington.