White Suburbanites Won’t Be Enough in Georgia

Progressives’ message in the Senate runoffs could find traction in an unexpected place.

Georgia Democrats are in a door-knocking, lit-dropping frenzy. Many of them are focused on turning out voters in the upper-middle-class neighborhoods of suburban Atlanta—the voters who helped flip the state to Joe Biden in November, and who are widely considered the key group for Democrats to reach. But not Ben Davidson. Ben Davidson is hitting the apartments.

The 34-year-old sales manager, one of the leaders of a local progressive group called Georgians for Registration and Increased Turnout, or GRIT, has spent virtually all his free hours since Election Day inside the diverse and mostly low-income apartment complexes dotting the southeast edge of Cobb County, a big suburb northwest of Atlanta. At each door, Davidson asks residents about COVID-19—whether they’ve still got a job, plenty of food, enough money for rent. He asks whether they’d like to get another $1,200 check from the government. They typically respond with something along the lines of “Hell yeah,” Davidson told me. So he tells them to vote for Democrats Jon Ossoff and Raphael Warnock on January 5. “If we want COVID relief, we have to get these guys in office,” he says to the residents.

Progressives such as Davidson have a theory for Democratic success that goes something like this: If candidates campaign on a populist economic agenda that appeals to all working-class Americans, they’ll see a boom in turnout. So far, that theory has not borne fruit, at least not on any mass scale. But the Georgia runoffs, which will determine Senate control, could be different. Democrats have something specific and concrete to offer voters that they didn’t have in elections past: When they win back the chamber, everyone gets a check. If groups like Davidson’s can boost turnout, they’ll have validated progressives’ theory—and demonstrated that Democrats can win suburban voters even without Donald Trump on the ballot.

The runoffs will likely be close, if the vote tallies from November are any indication. But Democrats face two major obstacles to victory: Trump, a singular catalyst for left-wing turnout, will be on the sidelines in this election, and the Democratic Senate candidates underperformed Biden in Georgia. One theory for this underperformance is that a lot of well-off, college-educated suburbanites who voted Biden for president backed Republicans down the rest of the ballot.

For Democrats to win both Senate races, they need to remobilize the voters who went to the polls in November, and get some new ones too. One option is to frame the runoffs as equal in consequence to the presidential election: A Republican Senate can be expected to block basically everything on the Biden agenda. Another option is to argue that the financial activities of the Republican incumbents, Kelly Loeffler and David Perdue, make them untrustworthy and out of touch with Georgia voters.

But progressives want the party to focus on the possibilities for pandemic relief under a Democratic Senate. Through the CARES Act passed in the spring, Republicans and Democrats unanimously approved $1,200 stimulus checks for qualifying Americans and $600-a-week enhanced unemployment benefits, which expired in July. Americans have struggled to pay their bills and waited in lines outside food banks for months as Congress has made slow progress on a new relief package. Stimulus checks are a sticking point: Most Republicans (and some Democrats) are opposed to direct payments, and it’s still unclear whether the package under negotiation will include them. Perdue and Loeffler initially opposed direct payments to Americans in early spring. While both might ultimately support the new package if it comes for a vote, neither has made clear where they currently stand on direct assistance, and a new round of stimulus checks could be less generous than the first. Democrats hope to pass more COVID-19 relief once Biden is inaugurated next month.

“The more that Democrats are able to paint Republicans as plutocrats who don’t care about working-class and middle-class families,” the more successful they’ll be, Waleed Shahid, the communications director for the progressive group Justice Democrats, told me.

This message could find traction in an unexpected place: America’s rapidly changing suburbs. It’s how GRIT, which was formed by a group of local activists after Election Day to focus on voter registration, is targeting new and low-propensity voters. “We follow the Stacey Abrams playbook here,” Davidson told me, referencing the former Georgia state lawmaker’s efforts to mobilize and expand the Democratic base. He and other GRIT members have knocked on thousands of doors in the apartment buildings along Highway 285, generally considered the borderline between the state capital and its suburbs. These apartments are zoned as part of the latter region, but residents here are not the upper-middle-class Ward and June Cleaver of suburban myth. Instead, the buildings contain high concentrations of young people, people of color, and lower-income workers—many of them unregistered to vote. Many residents are employed in the service industry, many are immigrants, and many move around a lot, which means they’re hard to target using traditional canvassing methods.

These Georgians are the new suburbanites—people who, a decade ago, would have typically lived in a major city, but who have moved to the inner-ring suburbs, where housing can be more affordable, Ernest McGowen, a political-science professor at the University of Richmond, told me. Suburbs around the country are becoming more diverse, in part thanks to residents such as these, and the regions’ evolution couldn’t come at a more politically advantageous time for Democrats.

At least some of the anti-Trump voters whom Democrats have come to rely on may soon return to the Republican Party. In a swing state such as Georgia, where victory happens at the margins, this dynamic should be worrisome for Democrats. But organizers can help compensate for a deficit if they turn out voters like those living in the apartments. They are “Democrats’ bread and butter,” Davidson told me. GRIT’s policy to win them over: “Knock every damn door.”

The Georgians whom Davidson and his teammates meet inside these developments are eager for another round of cash assistance, he said. They perk up, too, when they hear about Daniel Blackman, a candidate for the Georgia Public Service Commission—and the only other Democrat who will be on the ballot in January—who’s campaigned on lowering utility rates. These ideas appeal to working people because if you’re earning only a couple thousand dollars a month, even small changes in monthly payments can make a monumental difference.

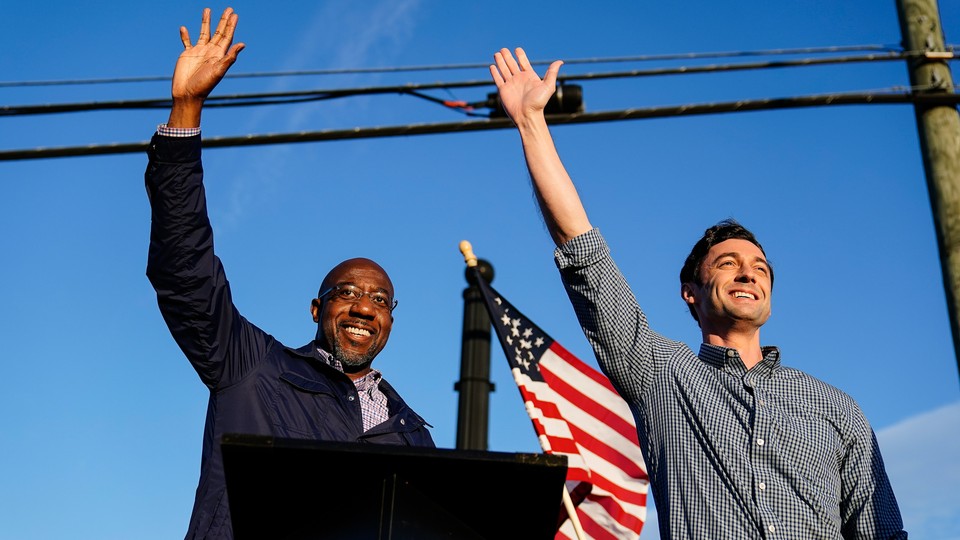

Ossoff and Warnock are deploying the same message, hammering COVID-19 relief in their tweets, ads, and television appearances. “Get on a plane to Washington and vote for $1,200 stimulus checks for your constituents who are hurting right now, Senator,” Ossoff said in a recent interview on MSNBC.

Progressives have been urging Democrats to talk like this. For multiple election cycles now, leftists have insisted that a working-class revolution could be imminent, if only Democratic candidates would embrace a message of economic populism. But this approach didn’t even work for their standard-bearer: Bernie Sanders twice ran for president on a platform of raising wages and workers’ rights, arguing that he would awaken a legion of brand-new voters and send them to the polls. But those voters never showed up, and, as you may have noticed, Sanders is not currently the president-elect. Progressive House candidates campaigning similarly in swing states were mostly unsuccessful in 2018 and 2020. This message may not work as well as progressives hope.

And despite Biden’s win, Republicans still have it easier than Democrats in Georgia. For the runoff elections, Loeffler and Perdue simply need to reprise their November turnout, which was higher than Democrats’. “Fundamentally, this is still a state that wants to be a little bit Republican,” the GOP strategist Liam Donovan told me.

But the give-people-money approach is widely popular across the country and across party lines. In Georgia, 63 percent of probable runoff voters said they would be more likely to vote for a candidate who commits to passing an additional $1,200 relief check, according to a recent survey from the progressive polling firm Data for Progress.

In the Atlanta suburbs, Davidson and his GRIT teammates signed up some 200 new Democratic voters before registration closed on December 7. They’re holding multiple events every week at complexes all along the highway. Roughly one-third of the Georgians Davidson meets haven’t heard about the elections before, he estimates, but he’ll keep making the case. He needs them to show up on January 5, these suburbanites who are often excluded from voter outreach, and left out of the national conversation. Without them, Democrats may not be able to win.