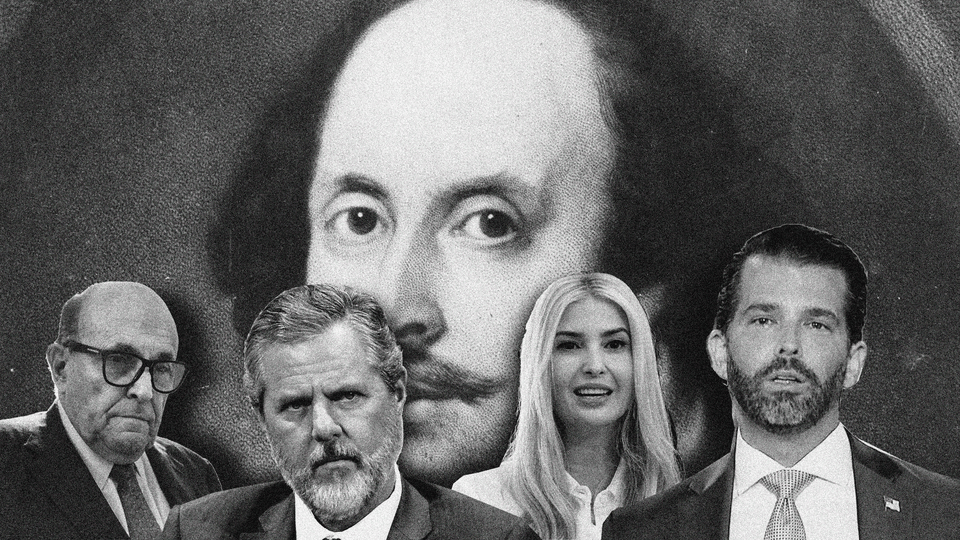

Trump’s Enablers Will Meet Their Shakespearean Ends

The Bard had a rich sense of the creeps and criminals, sycophants and slimeballs, weirdos and wing nuts who hang around power.

It is a mark of these astounding times that news of heated meetings at the White House considering, among other things, the confiscation of voting machines, declaration of martial law, and use of the military to preside over an election outcome more to the president’s liking were met with a collective yawn by the American people. The news of the FDA’s approval of the Moderna vaccine for the coronavirus was much more enthralling, and recipes for single batches of holiday punch, suitable for COVID-imposed isolation, were more immediately relevant.

This could indicate the apathy of the American people, battered by President Donald Trump’s antics, the pandemic, and an imperiled economy. More likely, it represents a reasoned confidence that if Trump were to order General Mark Milley, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, to arrest President-elect Joe Biden and occupy the capitals of Wisconsin, Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Arizona, the stocky general would report sick for the next 30 days. Judges would block the orders, governors would laugh at them, Republican senators would demurely pretend they had not heard of them. So is there nothing left to be said about the final scene of the final act of this dismal play?

Trump, it bears repeating, is no Shakespearean villain—he is too willful, ignorant, undisciplined, and shallow for that. What we are watching is not the despair of Macbeth as he learns that Birnam Wood to Dunsinane Hill doth come and that Macduff was not indeed born of woman. It is, rather, a malignant narcissist’s psyche collapsing in on its hollow core. That process may be of clinical or purely malevolent interest, but it’s not the stuff of tragedy, because Trump is really only a few shards of a genuine human being.

But Shakespeare does have something yet to offer us about this moment when treason against the constitutional order is a matter for serious Oval Office debate. The Bard had a rich sense of the creeps and criminals, sycophants and slimeballs, weirdos and wing nuts who hang around power. And although it is true that in an awful lot of his plays the good guys end up poorly, it is reassuring to know that a lot of the toadies, demagogues, and opportunists get theirs in the end.

Take some of the courtiers to Richard II, a weak and easily flattered king. “Caterpillars of the commonwealth,” the usurper Henry Bolingbroke calls them before dispatching them to the block. They go with a snarl. The duke of Buckingham, faithful aide to Richard III, is at least remorseful when his boss sends him off to meet the headsman: “Come lead me, officers, to the block of shame. / Wrong hath but wrong, and blame the due of blame.” Of course, members of Trump’s entourage need not fear so gruesome a fate, and I do not wish bodily harm on any of them. Yet gloomy thoughts of a similar kind may have occurred to more than one of the president’s appointees when he heard the swishing of the Twitter ax descending on his exposed neck.

Of course, the cast of characters in Trump’s mad court was much wider than this. Pious hypocrites? Jerry Falwell Jr. could probably take a lesson or two from Angelo in Measure for Measure. After preaching a rather austere morality (death as punishment for premarital sex), he tries to commit rape and judicial murder, thinking he can cover up his adventures. He cannot. “That Angelo is an adulterous thief, / An hypocrite, a virgin-violator, / Is it not strange, and strange?” Well, quite, and while Falwell is alleged to have merely watched rather than indulged, the ruin is similar, and equally well deserved.

But it would be wrong to think that bad behavior in Trump’s court is a masculine matter only. There is, after all, an odd mix of female political advisers, television personalities, and preachers who have, as does Queen Margaret, “a tiger’s heart wrapped in a woman’s hide.” They have not gone mad, as Margaret does, but they do have Joan of Arc’s misplaced self-confidence, and there is time yet.

And then there is the mob. In Henry VI, Part 2, the followers of Jack Cade—played in this production by Rudy Giuliani—call for killing all the lawyers. They also seem to have a desire to kill anyone who can speak French or Latin, or who has any learning at all. But Jack Cade ends up with his head on display to warn others about the price of rebellion against lawful order, as do so many in Shakespeare’s plays. More interesting are the Roman mobs that love Caesar, then approve his murder, then, after some masterful manipulation by Mark Antony, turn on Brutus and the conspirators. They are not particularly picky. They kill Cinna the poet rather than Cinna the senator, declaring that it’s all the same—kill him for bad verse. The mob cheers Coriolanus and then expels him from Rome, only to tremble in terror when he comes back with the enemies of Rome in orderly ranks at his back.

But if Shakespeare takes a dim view of the Make Rome Great Again populace, his scorn for their manipulators is far deeper. Mark Antony is brilliant at crying havoc and letting slip the dogs of war, but he throws away his leading role in the Roman state once he meets Cleopatra. His lust derails a promising career as aspiring global dictator.

The Trump family should not take a great deal of comfort from Shakespeare, either. Yes, Henry V succeeds Henry IV (albeit not without some difficulty), but orderly succession is the exception in his plays. And indeed, Henry V’s own son, Henry VI, turns out to be something of a political dope. Inheriting power is tougher than it looks. Harry Percy finds that out when his dad, the earl of Northumberland, is inexplicably late for the decisive battle. So much for paternal affection. Percy’s last words after losing his duel with Prince Hal are that he will shortly be “food for—” “Worms,” Hal helpfully finishes the sentence. Don Jr., Eric, Ivanka, and Jared take note.

Finally, the henchmen. They’re lucky if they get sent packing with their heads still attached to their shoulders:

They love not poison that do poison need.

Nor do I thee …

With Cain go wander through shades of night,

And never show thy head by day nor light.

But then again, hireling thugs have not usually been all that happy to this point in their lives anyway:

I am one, my liege

Whom the vile blows and buffets of the world

Hath so incensed, that I am reckless what

I do to spite the world.

It would be pleasant to contemplate a parade of senatorial and congressional lickspittles, craven fixers, nutcase advisers, and unprincipled hangers-on meeting their comeuppance, albeit in considerably less stark terms than befalls most Shakespearean characters. No doubt many will be able to minimize the damage done by their association with Trump. Many will safely monetize their government experience (Dancing With the Stars was Sean Spicer’s creative effort in that direction), pretending that their service had nothing but the purest motives behind it, and that they either did not know about the seditious inclinations and plots erupting at this very moment or opposed them. But let’s face it: Once the play is over, the supporting roles rarely get reevaluated, and all the lesser villains can hope for, like Iago, is a bit of wonder at their motivations and eventual fate.

And what of Trump himself? How might Shakespeare summarize his presidency? Let me suggest this: “A tale / Told by an idiot, full of sound and fury / Signifying nothing.”