France Knows How This Ends

Polarization, anger, division—French history offers a warning for what might come after Donald Trump.

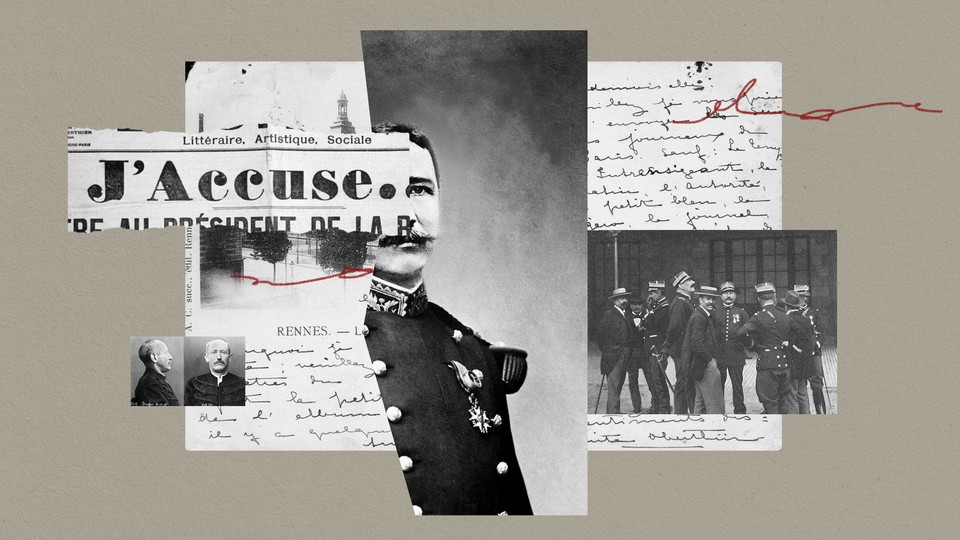

A Jewish military officer wrongfully convicted of treason. A years-long psychodrama that permanently polarized an entire society—communities, friends, even families. A politics of anger and emotion designed to insult the very notion of truth. A divide that only grew with time. A reconciliation that never was. A frenzied right wing that turned to violence when it failed at the ballot box.

This was the Dreyfus affair, the signature scandal of fin de siècle France, aspects of which Americans might recognize as we arrive at the end of Donald Trump’s presidency: After decades of cascading political crises, debilitating financial scandals, and rising anti-Semitism, the Dreyfus affair saw the emergence of political surreality, an alternate universe of hateful irrationality and militarized lies that captured the minds of nearly half the population.

That period in France, known as the Third Republic, never resulted in any reconciliation. It turned out to be impossible to compromise with those who not only rejected the truth but also found the truth offensive, a kind of existential threat. The social divide simply grew wider and wider, to the point where bridging the gap became a futile proposition. Even the national mobilization in World War I was not enough to create a durable unity; the wounds of the past proved impossible to heal. In fact, “unity” turned out to be the wrong goal to pursue. What mattered was defending the republic’s values, a defense never made forcefully enough.

As a historian of modern France, I’ve followed with great interest the innumerable comparisons drawn between Trumpism and Nazism that began even before Trump took office: the endless debate over whether Trump can be called a “fascist” (I would say yes), whether American society today resembles Weimar Germany before it fell to the Nazis (I would say no), and whether we can really say that the Republican Party is just a confederation of “collaborators” (of course we can).

All historical analogies are flawed, and they might not mean much at all. Even if they underscore the gravity of the moment, they often obscure its causes and might, in fact, prevent us from seeing them. Trump might be leaving office, but his followers are here to stay, as their numbers and conviction make clear. In seeking to understand Trump, and Trumpism, we have preferred to tell ourselves stories about violent rupture and hostile takeovers—of Hitler’s rise, of Nazism’s threat, of the perils of collaboration—but not so much about the valorization of falsehood and a republic that ignores, and even embraces, its own terminal impotence. That is the story of France’s Third Republic and its defining psychodrama.

The Third Republic was born in a moment of trauma, in the aftermath of France’s total humiliation in the Franco-Prussian War. It was a return to the venerated ideals of the French Revolution after 18 years of imperial Bonapartism, and nobody, not even its first president, expected the new republic to last as long as it did—70 years, longer than any other system of government in modern French history, including the current regime, which began in 1958. This era, unlike Weimar Germany, which lasted only from 1918 to 1933, was a continuous system of government that spanned several generations of political actors. It’s possible to trace recurrent themes in that time, some of which resemble those in contemporary America.

What is most important to remember about the Third Republic is that, as long-lasting as it might have been, it was a parliamentary system constantly stalled in political gridlock. Its credibility was regularly called into question by a number of major financial scandals, and the French Parliament overthrew individual governments for often-trivial reasons, petty score settling, or insider politicking. Between July 1909, the bitter end of Georges Clemenceau’s first premiership, and August 1914, the start of World War I, there were 11 different governments. Prominent ministers—some of whom became celebrities in a game of musical chairs—often put off dealing with the pressing issues of the day, either because they would likely not have had sufficient time in office to do anything concrete or because they were unwilling to assume the political liability. The goal was to stay in power by whatever means.

Despite its unending political intractability, the Third Republic was also a time of unprecedented social advancement in the lives of ordinary people, an era marked by ruthless colonial expansion overseas and cultural refinement at home. The time of the Dreyfus affair, after all, was also the Belle Époque, the world that appears in the canvases of Renoir and in the novels of Marcel Proust, perhaps the greatest chronicler of the age, and a time whose optimistic spirit was embodied in the Eiffel Tower, the tallest structure in the world on its completion in 1889. Yet, much like in America today, there was a self-absorbed intellectual establishment obsessed with decline and the mysterious disease of “decadence,” which was spoken of in the same pompous outrage that our own pundits use to decry what happens on Ivy League campuses or in major newsrooms.

In the end, the opportunism and the cynicism of political elites earned them the distrust of both ordinary voters and the bureaucrats left to run things when they themselves would not. What emerged was a “politics of resentment,” to use the phrase of the historian Philip Nord, who has written about the way shopkeepers, peasants, and other small-business owners grew disillusioned with the Third Republic and its lofty ideals, which to them seemed hollow, totally out of touch with the economic challenges they faced. The spectacular crash of the Union Générale bank in 1882 triggered an economic downturn that would take years to overcome; this, and the corruption of the Panama scandal just four years later, might be seen as 19th-century versions of 2008, economic crises whose root causes were similarly ignored by the elite and, among the masses, blamed on the Jews.

Beyond mere themes, there were multiple Trumpian moments and characters in the Third Republic as well, most notably Georges Boulanger, the swashbuckling, garish hard-line nationalist general who seemed to emerge from nowhere and launched a populist movement of mass appeal, an anti-republican crusade that nearly toppled the republic in 1889. Boulangism did not last politically, but it represented a new fault line in French society: a powerful right-wing bloc that united some in the working class along with conservative Catholics and the remnants of the old nobility. It only radicalized from there a few years later, and the Dreyfus affair was the moment when what was left of the social fabric definitively unraveled.

When historians now think about the Dreyfus affair—which saw the wrongful conviction of Alfred Dreyfus, a Jewish military captain accused of treason and forced to serve a lengthy prison sentence on Devil’s Island in French Guiana—we rightly remember it as the most significant example of political anti-Semitism in Europe before the Holocaust. It was the event that inspired the young Theodor Herzl to outline his vision of what we now know as Zionism and, as Hannah Arendt later argued (not entirely convincingly), a 19th-century nightmare that somehow foretold the horrors of the 20th century to come.

But the reason this episode bears revisiting today is not simply to compare French anti-Semitism then to American anti-Semitism now, although it’s worth remembering that the deadliest series of attacks on American Jews in our history has taken place during this administration. What is especially useful to remember about the Dreyfus affair now is the point of no return it represented, the repugnant embrace of lies by one half of society, educated people who were not ignorant but who had simply ceased to care. For them, the truth was irrelevant; what mattered was preserving their vision of the nation, regardless of the facts.

From start to finish, the Dreyfus affair was a seemingly endless social drama. Much like the Trump presidency, it was an all-consuming, emotional experience that left no aspect of public or even private life untouched. It would be hard to overstate the polarization it triggered in France, which found its population split over the fate of an obscure officer hardly anyone had heard of before the episode began. Over time, the controversy far transcended the case of Dreyfus himself, as there was evidence relatively early on proving that he had been framed. None of it mattered.

In some ways, the Dreyfus affair was the culmination of an age-old clash begun by the French Revolution: On one side were the defenders of the republic and its “universal” values, on the other the anti-republican faction that preferred the grandeur of the monarchy, the sanctity of the Church, and the prestige of the military. For many opponents of Dreyfus, the scandal was about defending the military’s honor at all costs, but this is much too simple a reading of their intent, as is any single explanation given for Trump’s appeal and the support he continues to enjoy among his followers, no matter how much evidence is shown to them or how many of his lies are exposed. Then, as now, these people had undertaken a deliberate embrace of irrationality, an almost primal flouting of decency and civilized norms, merely because that was possible, and because there were never any real consequences. The writer Charles Maurras, one of the most virulent anti-Semites and anti-Dreyfusards of the time, was even named to the Académie Française in 1938, the nation’s highest literary honor.

In the end, the institutions of the republic prevailed, just as ours have, at least for the moment. Dreyfus was exonerated, although he should never have been convicted in the first place; Congress officially certified the results of the 2020 election, although not until after a putsch attempt launched by the sitting president and carried out by his followers. But there was never any reconciliation then, just as there will not be now. Those who had opposed Dreyfus, even in the face of incontrovertible evidence, were permitted to remain in their fanciful universe of illusions and lies.

There might not be a clear line between the right wing that radicalized during the Dreyfus affair and the events of the 1930s, but what began as something of a club for like-minded bigots, locked in the lie of Dreyfus’s “guilt,” then started inspiring actual violence. Groups born in the scandal, notably the Action Française, beat up Jewish politicians such as Léon Blum, France’s first-ever Jewish prime minister, who nearly died from a 1936 attack, and they took center stage in a February 1934 insurrection attempt that looked quite a lot like the scenes from the Capitol invasion this month.

We should not indulge the illusions of our own anti-Dreyfusards, yet I fear we will. By now, it seems fairly clear that those who stormed the Capitol and those proven to have encouraged that violent spectacle are likely to be brought to justice, at least in some form. But this might not solve the deeper problem, which is that so many in Trump’s mob—like so many of his supporters in general—remain comfortably ensconced in the mansion of lies their champion has built. As we have seen for years on end, any attempt to expose those lies with facts or evidence of any kind is a fool’s errand. These people deliberately inhabit an alternate universe because it makes them feel powerful, because it frustrates their enemies, and, in the end, because they can.

Ever since the events of January 6, the line among certain Democrats has been that there can be “no healing without accountability.” But this is naive. There can be no accountability for those who engage in surreality, the dark province in which the world is apparently run by a cabal of prominent pedophiles and where Trump somehow retained the White House in a landslide. As long as the president’s supporters insult the notion of objective truth, coddled by conspiracy theories and social-media networks that simulate a sense of community, there will be no common ground to seek, no “America” to reclaim. Perhaps there never was a unified “America,” but once upon a time there was a mutual reality. Until there is again, things will continue to deteriorate. If the Dreyfus affair and France’s Third Republic have any echo today, it is that we have not yet seen the worst.

Historical analogies have their limits, of course, and it is next to impossible to “learn” from history as a useful corrective. But if the past rarely offers lessons, sometimes it offers warnings.