When the polio vaccine was declared safe and effective, the news was met with jubilant celebration. Church bells rang across the nation, and factories blew their whistles. “Polio routed!” newspaper headlines exclaimed. “An historic victory,” “monumental,” “sensational,” newscasters declared. People erupted with joy across the United States. Some danced in the streets; others wept. Kids were sent home from school to celebrate.

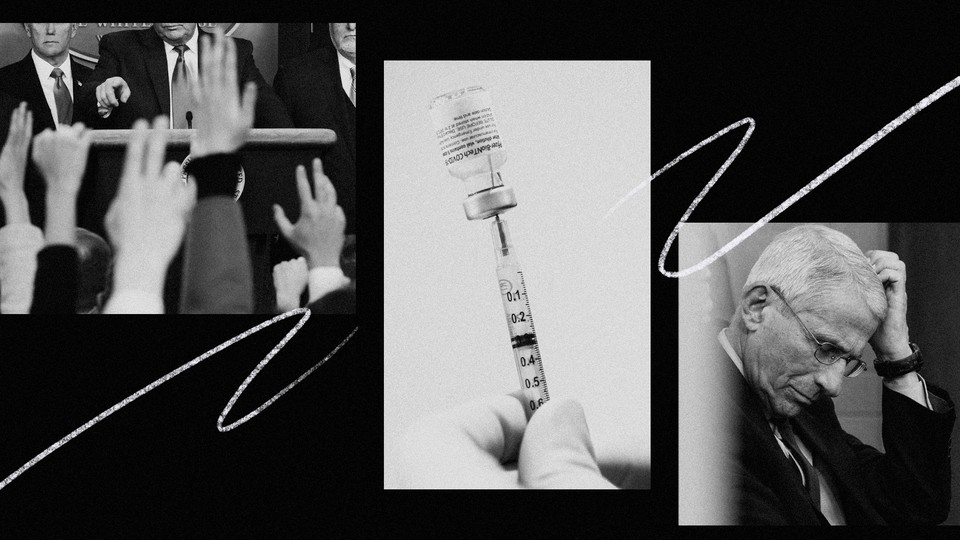

One might have expected the initial approval of the coronavirus vaccines to spark similar jubilation—especially after a brutal pandemic year. But that didn’t happen. Instead, the steady drumbeat of good news about the vaccines has been met with a chorus of relentless pessimism.

The problem is not that the good news isn’t being reported, or that we should throw caution to the wind just yet. It’s that neither the reporting nor the public-health messaging has reflected the truly amazing reality of these vaccines. There is nothing wrong with realism and caution, but effective communication requires a sense of proportion—distinguishing between due alarm and alarmism; warranted, measured caution and doombait; worst-case scenarios and claims of impending catastrophe. We need to be able to celebrate profoundly positive news while noting the work that still lies ahead. However, instead of balanced optimism since the launch of the vaccines, the public has been offered a lot of misguided fretting over new virus variants, subjected to misleading debates about the inferiority of certain vaccines, and presented with long lists of things vaccinated people still cannot do, while media outlets wonder whether the pandemic will ever end.

This pessimism is sapping people of energy to get through the winter, and the rest of this pandemic. Anti-vaccination groups and those opposing the current public-health measures have been vigorously amplifying the pessimistic messages—especially the idea that getting vaccinated doesn’t mean being able to do more—telling their audiences that there is no point in compliance, or in eventual vaccination, because it will not lead to any positive changes. They are using the moment and the messaging to deepen mistrust of public-health authorities, accusing them of moving the goalposts and implying that we’re being conned. Either the vaccines aren’t as good as claimed, they suggest, or the real goal of pandemic-safety measures is to control the public, not the virus.

Five key fallacies and pitfalls have affected public-health messaging, as well as media coverage, and have played an outsize role in derailing an effective pandemic response. These problems were deepened by the ways that we—the public—developed to cope with a dreadful situation under great uncertainty. And now, even as vaccines offer brilliant hope, and even though, at least in the United States, we no longer have to deal with the problem of a misinformer in chief, some officials and media outlets are repeating many of the same mistakes in handling the vaccine rollout.

The pandemic has given us an unwelcome societal stress test, revealing the cracks and weaknesses in our institutions and our systems. Some of these are common to many contemporary problems, including political dysfunction and the way our public sphere operates. Others are more particular, though not exclusive, to the current challenge—including a gap between how academic research operates and how the public understands that research, and the ways in which the psychology of coping with the pandemic have distorted our response to it.

Recognizing all these dynamics is important, not only for seeing us through this pandemic—yes, it is going to end—but also to understand how our society functions, and how it fails. We need to start shoring up our defenses, not just against future pandemics but against all the myriad challenges we face—political, environmental, societal, and technological. None of these problems is impossible to remedy, but first we have to acknowledge them and start working to fix them—and we’re running out of time.

The past 12 months were incredibly challenging for almost everyone. Public-health officials were fighting a devastating pandemic and, at least in this country, an administration hell-bent on undermining them. The World Health Organization was not structured or funded for independence or agility, but still worked hard to contain the disease. Many researchers and experts noted the absence of timely and trustworthy guidelines from authorities, and tried to fill the void by communicating their findings directly to the public on social media. Reporters tried to keep the public informed under time and knowledge constraints, which were made more severe by the worsening media landscape. And the rest of us were trying to survive as best we could, looking for guidance where we could, and sharing information when we could, but always under difficult, murky conditions.

Despite all these good intentions, much of the public-health messaging has been profoundly counterproductive. In five specific ways, the assumptions made by public officials, the choices made by traditional media, the way our digital public sphere operates, and communication patterns between academic communities and the public proved flawed.

Risk Compensation

One of the most important problems undermining the pandemic response has been the mistrust and paternalism that some public-health agencies and experts have exhibited toward the public. A key reason for this stance seems to be that some experts feared that people would respond to something that increased their safety—such as masks, rapid tests, or vaccines—by behaving recklessly. They worried that a heightened sense of safety would lead members of the public to take risks that would not just undermine any gains, but reverse them.

The theory that things that improve our safety might provide a false sense of security and lead to reckless behavior is attractive—it’s contrarian and clever, and fits the “here’s something surprising we smart folks thought about” mold that appeals to, well, people who think of themselves as smart. Unsurprisingly, such fears have greeted efforts to persuade the public to adopt almost every advance in safety, including seat belts, helmets, and condoms.

But time and again, the numbers tell a different story: Even if safety improvements cause a few people to behave recklessly, the benefits overwhelm the ill effects. In any case, most people are already interested in staying safe from a dangerous pathogen. Further, even at the beginning of the pandemic, sociological theory predicted that wearing masks would be associated with increased adherence to other precautionary measures—people interested in staying safe are interested in staying safe—and empirical research quickly confirmed exactly that. Unfortunately, though, the theory of risk compensation—and its implicit assumptions—continue to haunt our approach, in part because there hasn’t been a reckoning with the initial missteps.

Rules in Place of Mechanisms and Intuitions

Much of the public messaging focused on offering a series of clear rules to ordinary people, instead of explaining in detail the mechanisms of viral transmission for this pathogen. A focus on explaining transmission mechanisms, and updating our understanding over time, would have helped empower people to make informed calculations about risk in different settings. Instead, both the CDC and the WHO chose to offer fixed guidelines that lent a false sense of precision.

In the United States, the public was initially told that “close contact” meant coming within six feet of an infected individual, for 15 minutes or more. This messaging led to ridiculous gaming of the rules; some establishments moved people around at the 14th minute to avoid passing the threshold. It also led to situations in which people working indoors with others, but just outside the cutoff of six feet, felt that they could take their mask off. None of this made any practical sense. What happened at minute 16? Was seven feet okay? Faux precision isn’t more informative; it’s misleading.

All of this was complicated by the fact that key public-health agencies like the CDC and the WHO were late to acknowledge the importance of some key infection mechanisms, such as aerosol transmission. Even when they did so, the shift happened without a proportional change in the guidelines or the messaging—it was easy for the general public to miss its significance.

Frustrated by the lack of public communication from health authorities, I wrote an article last July on what we then knew about the transmission of this pathogen—including how it could be spread via aerosols that can float and accumulate, especially in poorly ventilated indoor spaces. To this day, I’m contacted by people who describe workplaces that are following the formal guidelines, but in ways that defy reason: They’ve installed plexiglass, but barred workers from opening their windows; they’ve mandated masks, but only when workers are within six feet of one another, while permitting them to be taken off indoors during breaks.

Perhaps worst of all, our messaging and guidelines elided the difference between outdoor and indoor spaces, where, given the importance of aerosol transmission, the same precautions should not apply. This is especially important because this pathogen is overdispersed: Much of the spread is driven by a few people infecting many others at once, while most people do not transmit the virus at all.

After I wrote an article explaining how overdispersion and super-spreading were driving the pandemic, I discovered that this mechanism had also been poorly explained. I was inundated by messages from people, including elected officials around the world, saying they had no idea that this was the case. None of it was secret—numerous academic papers and articles had been written about it—but it had not been integrated into our messaging or our guidelines despite its great importance.

Crucially, super-spreading isn’t equally distributed; poorly ventilated indoor spaces can facilitate the spread of the virus over longer distances, and in shorter periods of time, than the guidelines suggested, and help fuel the pandemic.

Outdoors? It’s the opposite.

There is a solid scientific reason for the fact that there are relatively few documented cases of transmission outdoors, even after a year of epidemiological work: The open air dilutes the virus very quickly, and the sun helps deactivate it, providing further protection. And super-spreading—the biggest driver of the pandemic— appears to be an exclusively indoor phenomenon. I’ve been tracking every report I can find for the past year, and have yet to find a confirmed super-spreading event that occurred solely outdoors. Such events might well have taken place, but if the risk were great enough to justify altering our lives, I would expect at least a few to have been documented by now.

And yet our guidelines do not reflect these differences, and our messaging has not helped people understand these facts so that they can make better choices. I published my first article pleading for parks to be kept open on April 7, 2020—but outdoor activities are still banned by some authorities today, a full year after this dreaded virus began to spread globally.

We’d have been much better off if we gave people a realistic intuition about this virus’s transmission mechanisms. Our public guidelines should have been more like Japan’s, which emphasize avoiding the three C’s—closed spaces, crowded places, and close contact—that are driving the pandemic.

Scolding and Shaming

Throughout the past year, traditional and social media have been caught up in a cycle of shaming—made worse by being so unscientific and misguided. How dare you go to the beach? newspapers have scolded us for months, despite lacking evidence that this posed any significant threat to public health. It wasn’t just talk: Many cities closed parks and outdoor recreational spaces, even as they kept open indoor dining and gyms. Just this month, UC Berkeley and the University of Massachusetts at Amherst both banned students from taking even solitary walks outdoors.

Even when authorities relax the rules a bit, they do not always follow through in a sensible manner. In the United Kingdom, after some locales finally started allowing children to play on playgrounds—something that was already way overdue—they quickly ruled that parents must not socialize while their kids have a normal moment. Why not? Who knows?

On social media, meanwhile, pictures of people outdoors without masks draw reprimands, insults, and confident predictions of super-spreading—and yet few note when super-spreading fails to follow.

While visible but low-risk activities attract the scolds, other actual risks—in workplaces and crowded households, exacerbated by the lack of testing or paid sick leave—are not as easily accessible to photographers. Stefan Baral, an associate epidemiology professor at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, says that it’s almost as if we’ve “designed a public-health response most suitable for higher-income” groups and the “Twitter generation”—stay home; have your groceries delivered; focus on the behaviors you can photograph and shame online—rather than provide the support and conditions necessary for more people to keep themselves safe.

And the viral videos shaming people for failing to take sensible precautions, such as wearing masks indoors, do not necessarily help. For one thing, fretting over the occasional person throwing a tantrum while going unmasked in a supermarket distorts the reality: Most of the public has been complying with mask wearing. Worse, shaming is often an ineffective way of getting people to change their behavior, and it entrenches polarization and discourages disclosure, making it harder to fight the virus. Instead, we should be emphasizing safer behavior and stressing how many people are doing their part, while encouraging others to do the same.

Harm Reduction

Amidst all the mistrust and the scolding, a crucial public-health concept fell by the wayside. Harm reduction is the recognition that if there is an unmet and yet crucial human need, we cannot simply wish it away; we need to advise people on how to do what they seek to do more safely. Risk can never be completely eliminated; life requires more than futile attempts to bring risk down to zero. Pretending we can will away complexities and trade-offs with absolutism is counterproductive. Consider abstinence-only education: Not letting teenagers know about ways to have safer sex results in more of them having sex with no protections.

As Julia Marcus, an epidemiologist and associate professor at Harvard Medical School, told me, “When officials assume that risks can be easily eliminated, they might neglect the other things that matter to people: staying fed and housed, being close to loved ones, or just enjoying their lives. Public health works best when it helps people find safer ways to get what they need and want.”

Another problem with absolutism is the “abstinence violation” effect, Joshua Barocas, an assistant professor at the Boston University School of Medicine and Infectious Diseases, told me. When we set perfection as the only option, it can cause people who fall short of that standard in one small, particular way to decide that they’ve already failed, and might as well give up entirely. Most people who have attempted a diet or a new exercise regimen are familiar with this psychological state. The better approach is encouraging risk reduction and layered mitigation—emphasizing that every little bit helps—while also recognizing that a risk-free life is neither possible nor desirable.

Socializing is not a luxury—kids need to play with one another, and adults need to interact. Your kids can play together outdoors, and outdoor time is the best chance to catch up with your neighbors is not just a sensible message; it’s a way to decrease transmission risks. Some kids will play and some adults will socialize no matter what the scolds say or public-health officials decree, and they’ll do it indoors, out of sight of the scolding.

And if they don’t? Then kids will be deprived of an essential activity, and adults will be deprived of human companionship. Socializing is perhaps the most important predictor of health and longevity, after not smoking and perhaps exercise and a healthy diet. We need to help people socialize more safely, not encourage them to stop socializing entirely.

The Balance Between Knowledge And Action

Last but not least, the pandemic response has been distorted by a poor balance between knowledge, risk, certainty, and action.

Sometimes, public-health authorities insisted that we did not know enough to act, when the preponderance of evidence already justified precautionary action. Wearing masks, for example, posed few downsides, and held the prospect of mitigating the exponential threat we faced. The wait for certainty hampered our response to airborne transmission, even though there was almost no evidence for—and increasing evidence against—the importance of fomites, or objects that can carry infection. And yet, we emphasized the risk of surface transmission while refusing to properly address the risk of airborne transmission, despite increasing evidence. The difference lay not in the level of evidence and scientific support for either theory—which, if anything, quickly tilted in favor of airborne transmission, and not fomites, being crucial—but in the fact that fomite transmission had been a key part of the medical canon, and airborne transmission had not.

Sometimes, experts and the public discussion failed to emphasize that we were balancing risks, as in the recurring cycles of debate over lockdowns or school openings. We should have done more to acknowledge that there were no good options, only trade-offs between different downsides. As a result, instead of recognizing the difficulty of the situation, too many people accused those on the other side of being callous and uncaring.

And sometimes, the way that academics communicate clashed with how the public constructs knowledge. In academia, publishing is the coin of the realm, and it is often done through rejecting the null hypothesis—meaning that many papers do not seek to prove something conclusively, but instead, to reject the possibility that a variable has no relationship with the effect they are measuring (beyond chance). If that sounds convoluted, it is—there are historical reasons for this methodology and big arguments within academia about its merits, but for the moment, this remains standard practice.

At crucial points during the pandemic, though, this resulted in mistranslations and fueled misunderstandings, which were further muddled by differing stances toward prior scientific knowledge and theory. Yes, we faced a novel coronavirus, but we should have started by assuming that we could make some reasonable projections from prior knowledge, while looking out for anything that might prove different. That prior experience should have made us mindful of seasonality, the key role of overdispersion, and aerosol transmission. A keen eye for what was different from the past would have alerted us earlier to the importance of presymptomatic transmission.

Thus, on January 14, 2020, the WHO stated that there was “no clear evidence of human-to-human transmission.” It should have said, “There is increasing likelihood that human-to-human transmission is taking place, but we haven’t yet proven this, because we have no access to Wuhan, China.” (Cases were already popping up around the world at that point.) Acting as if there was human-to-human transmission during the early weeks of the pandemic would have been wise and preventive.

Later that spring, WHO officials stated that there was “currently no evidence that people who have recovered from COVID-19 and have antibodies are protected from a second infection,” producing many articles laden with panic and despair. Instead, it should have said: “We expect the immune system to function against this virus, and to provide some immunity for some period of time, but it is still hard to know specifics because it is so early.”

Similarly, since the vaccines were announced, too many statements have emphasized that we don’t yet know if vaccines prevent transmission. Instead, public-health authorities should have said that we have many reasons to expect, and increasing amounts of data to suggest, that vaccines will blunt infectiousness, but that we’re waiting for additional data to be more precise about it. That’s been unfortunate, because while many, many things have gone wrong during this pandemic, the vaccines are one thing that has gone very, very right.

As late as April 2020, Anthony Fauci was slammed for being too optimistic for suggesting we might plausibly have vaccines in a year to 18 months. We had vaccines much, much sooner than that: The first two vaccine trials concluded a mere eight months after the WHO declared a pandemic in March 2020.

Moreover, they have delivered spectacular results. In June 2020, the FDA said a vaccine that was merely 50 percent efficacious in preventing symptomatic COVID-19 would receive emergency approval—that such a benefit would be sufficient to justify shipping it out immediately. Just a few months after that, the trials of the Moderna and Pfizer vaccines concluded by reporting not just a stunning 95 percent efficacy, but also a complete elimination of hospitalization or death among the vaccinated. Even severe disease was practically gone: The lone case classified as “severe” among 30,000 vaccinated individuals in the trials was so mild that the patient needed no medical care, and her case would not have been considered severe if her oxygen saturation had been a single percent higher.

These are exhilarating developments, because global, widespread, and rapid vaccination is our way out of this pandemic. Vaccines that drastically reduce hospitalizations and deaths, and that diminish even severe disease to a rare event, are the closest things we have had in this pandemic to a miracle—though of course they are the product of scientific research, creativity, and hard work. They are going to be the panacea and the endgame.

And yet, two months into an accelerating vaccination campaign in the United States, it would be hard to blame people if they missed the news that things are getting better.

Yes, there are new variants of the virus, which may eventually require booster shots, but at least so far, the existing vaccines are standing up to them well—very, very well. Manufacturers are already working on new vaccines or variant-focused booster versions, in case they prove necessary, and the authorizing agencies are ready for a quick turnaround if and when updates are needed. Reports from places that have vaccinated large numbers of individuals, and even trials in places where variants are widespread, are exceedingly encouraging, with dramatic reductions in cases and, crucially, hospitalizations and deaths among the vaccinated. Global equity and access to vaccines remain crucial concerns, but the supply is increasing.

Here in the United States, despite the rocky rollout and the need to smooth access and ensure equity, it’s become clear that toward the end of spring 2021, supply will be more than sufficient. It may sound hard to believe today, as many who are desperate for vaccinations await their turn, but in the near future, we may have to discuss what to do with excess doses.

So why isn’t this story more widely appreciated?

Part of the problem with the vaccines was the timing—the trials concluded immediately after the U.S. election, and their results got overshadowed in the weeks of political turmoil. The first, modest headline announcing the Pfizer-BioNTech results in The New York Times was a single column, “Vaccine Is Over 90% Effective, Pfizer’s Early Data Says,” below a banner headline spanning the page: “BIDEN CALLS FOR UNITED FRONT AS VIRUS RAGES.” That was both understandable—the nation was weary—and a loss for the public.

Just a few days later, Moderna reported a similar 94.5 percent efficacy. If anything, that provided even more cause for celebration, because it confirmed that the stunning numbers coming out of Pfizer weren’t a fluke. But, still amid the political turmoil, the Moderna report got a mere two columns on The New York Times’ front page with an equally modest headline: “Another Vaccine Appears to Work Against the Virus.”

So we didn’t get our initial vaccine jubilation.

But as soon as we began vaccinating people, articles started warning the newly vaccinated about all they could not do. “COVID-19 Vaccine Doesn’t Mean You Can Party Like It’s 1999,” one headline admonished. And the buzzkill has continued right up to the present. “You’re fully vaccinated against the coronavirus—now what? Don’t expect to shed your mask and get back to normal activities right away,” began a recent Associated Press story.

People might well want to party after being vaccinated. Those shots will expand what we can do, first in our private lives and among other vaccinated people, and then, gradually, in our public lives as well. But once again, the authorities and the media seem more worried about potentially reckless behavior among the vaccinated, and about telling them what not to do, than with providing nuanced guidance reflecting trade-offs, uncertainty, and a recognition that vaccination can change behavior. No guideline can cover every situation, but careful, accurate, and updated information can empower everyone.

Take the messaging and public conversation around transmission risks from vaccinated people. It is, of course, important to be alert to such considerations: Many vaccines are “leaky” in that they prevent disease or severe disease, but not infection and transmission. In fact, completely blocking all infection—what’s often called “sterilizing immunity”—is a difficult goal, and something even many highly effective vaccines don’t attain, but that doesn’t stop them from being extremely useful.

As Paul Sax, an infectious-disease doctor at Boston’s Brigham & Women’s Hospital, put it in early December, it would be enormously surprising “if these highly effective vaccines didn’t also make people less likely to transmit.” From multiple studies, we already knew that asymptomatic individuals—those who never developed COVID-19 despite being infected—were much less likely to transmit the virus. The vaccine trials were reporting 95 percent reductions in any form of symptomatic disease. In December, we learned that Moderna had swabbed some portion of trial participants to detect asymptomatic, silent infections, and found an almost two-thirds reduction even in such cases. The good news kept pouring in. Multiple studies found that, even in those few cases where breakthrough disease occurred in vaccinated people, their viral loads were lower—which correlates with lower rates of transmission. Data from vaccinated populations further confirmed what many experts expected all along: Of course these vaccines reduce transmission.

And yet, from the beginning, a good chunk of the public-facing messaging and news articles implied or claimed that vaccines won’t protect you against infecting other people or that we didn’t know if they would, when both were false. I found myself trying to convince people in my own social network that vaccines weren’t useless against transmission, and being bombarded on social media with claims that they were.

What went wrong? The same thing that’s going wrong right now with the reporting on whether vaccines will protect recipients against the new viral variants. Some outlets emphasize the worst or misinterpret the research. Some public-health officials are wary of encouraging the relaxation of any precautions. Some prominent experts on social media—even those with seemingly solid credentials—tend to respond to everything with alarm and sirens. So the message that got heard was that vaccines will not prevent transmission, or that they won’t work against new variants, or that we don’t know if they will. What the public needs to hear, though, is that based on existing data, we expect them to work fairly well—but we’ll learn more about precisely how effective they’ll be over time, and that tweaks may make them even better.

A year into the pandemic, we’re still repeating the same mistakes.

The top-down messaging is not the only problem. The scolding, the strictness, the inability to discuss trade-offs, and the accusations of not caring about people dying not only have an enthusiastic audience, but portions of the public engage in these behaviors themselves. Maybe that’s partly because proclaiming the importance of individual actions makes us feel as if we are in the driver’s seat, despite all the uncertainty.

Psychologists talk about the “locus of control”—the strength of belief in control over your own destiny. They distinguish between people with more of an internal-control orientation—who believe that they are the primary actors—and those with an external one, who believe that society, fate, and other factors beyond their control greatly influence what happens to us. This focus on individual control goes along with something called the “fundamental attribution error”—when bad things happen to other people, we’re more likely to believe that they are personally at fault, but when they happen to us, we are more likely to blame the situation and circumstances beyond our control.

An individualistic locus of control is forged in the U.S. mythos—that we are a nation of strivers and people who pull ourselves up by our bootstraps. An internal-control orientation isn’t necessarily negative; it can facilitate resilience, rather than fatalism, by shifting the focus to what we can do as individuals even as things fall apart around us. This orientation seems to be common among children who not only survive but sometimes thrive in terrible situations—they take charge and have a go at it, and with some luck, pull through. It is probably even more attractive to educated, well-off people who feel that they have succeeded through their own actions.

You can see the attraction of an individualized, internal locus of control in a pandemic, as a pathogen without a cure spreads globally, interrupts our lives, makes us sick, and could prove fatal.

There have been very few things we could do at an individual level to reduce our risk beyond wearing masks, distancing, and disinfecting. The desire to exercise personal control against an invisible, pervasive enemy is likely why we’ve continued to emphasize scrubbing and cleaning surfaces, in what’s appropriately called “hygiene theater,” long after it became clear that fomites were not a key driver of the pandemic. Obsessive cleaning gave us something to do, and we weren’t about to give it up, even if it turned out to be useless. No wonder there was so much focus on telling others to stay home—even though it’s not a choice available to those who cannot work remotely—and so much scolding of those who dared to socialize or enjoy a moment outdoors.

And perhaps it was too much to expect a nation unwilling to release its tight grip on the bottle of bleach to greet the arrival of vaccines—however spectacular—by imagining the day we might start to let go of our masks.

The focus on individual actions has had its upsides, but it has also led to a sizable portion of pandemic victims being erased from public conversation. If our own actions drive everything, then some other individuals must be to blame when things go wrong for them. And throughout this pandemic, the mantra many of us kept repeating—“Wear a mask, stay home; wear a mask, stay home”—hid many of the real victims.

Study after study, in country after country, confirms that this disease has disproportionately hit the poor and minority groups, along with the elderly, who are particularly vulnerable to severe disease. Even among the elderly, though, those who are wealthier and enjoy greater access to health care have fared better.

The poor and minority groups are dying in disproportionately large numbers for the same reasons that they suffer from many other diseases: a lifetime of disadvantages, lack of access to health care, inferior working conditions, unsafe housing, and limited financial resources.

Many lacked the option of staying home precisely because they were working hard to enable others to do what they could not, by packing boxes, delivering groceries, producing food. And even those who could stay home faced other problems born of inequality: Crowded housing is associated with higher rates of COVID-19 infection and worse outcomes, likely because many of the essential workers who live in such housing bring the virus home to elderly relatives.

Individual responsibility certainly had a large role to play in fighting the pandemic, but many victims had little choice in what happened to them. By disproportionately focusing on individual choices, not only did we hide the real problem, but we failed to do more to provide safe working and living conditions for everyone.

For example, there has been a lot of consternation about indoor dining, an activity I certainly wouldn’t recommend. But even takeout and delivery can impose a terrible cost: One study of California found that line cooks are the highest-risk occupation for dying of COVID-19. Unless we provide restaurants with funds so they can stay closed, or provide restaurant workers with high-filtration masks, better ventilation, paid sick leave, frequent rapid testing, and other protections so that they can safely work, getting food to go can simply shift the risk to the most vulnerable. Unsafe workplaces may be low on our agenda, but they do pose a real danger. Bill Hanage, associate professor of epidemiology at Harvard, pointed me to a paper he co-authored: Workplace-safety complaints to OSHA—which oversees occupational-safety regulations—during the pandemic were predictive of increases in deaths 16 days later.

New data highlight the terrible toll of inequality: Life expectancy has decreased dramatically over the past year, with Black people losing the most from this disease, followed by members of the Hispanic community. Minorities are also more likely to die of COVID-19 at a younger age. But when the new CDC director, Rochelle Walensky, noted this terrible statistic, she immediately followed up by urging people to “continue to use proven prevention steps to slow the spread—wear a well-fitting mask, stay 6 ft away from those you do not live with, avoid crowds and poorly ventilated places, and wash hands often.”

Those recommendations aren’t wrong, but they are incomplete. None of these individual acts do enough to protect those to whom such choices aren’t available—and the CDC has yet to issue sufficient guidelines for workplace ventilation or to make higher-filtration masks mandatory, or even available, for essential workers. Nor are these proscriptions paired frequently enough with prescriptions: Socialize outdoors, keep parks open, and let children play with one another outdoors.

Vaccines are the tool that will end the pandemic. The story of their rollout combines some of our strengths and our weaknesses, revealing the limitations of the way we think and evaluate evidence, provide guidelines, and absorb and react to an uncertain and difficult situation.

But also, after a weary year, maybe it’s hard for everyone—including scientists, journalists, and public-health officials—to imagine the end, to have hope. We adjust to new conditions fairly quickly, even terrible new conditions. During this pandemic, we’ve adjusted to things many of us never thought were possible. Billions of people have led dramatically smaller, circumscribed lives, and dealt with closed schools, the inability to see loved ones, the loss of jobs, the absence of communal activities, and the threat and reality of illness and death.

Hope nourishes us during the worst times, but it is also dangerous. It upsets the delicate balance of survival—where we stop hoping and focus on getting by—and opens us up to crushing disappointment if things don’t pan out. After a terrible year, many things are understandably making it harder for us to dare to hope. But, especially in the United States, everything looks better by the day. Tragically, at least 28 million Americans have been confirmed to have been infected, but the real number is certainly much higher. By one estimate, as many as 80 million have already been infected with COVID-19, and many of those people now have some level of immunity. Another 46 million people have already received at least one dose of a vaccine, and we’re vaccinating millions more each day as the supply constraints ease. The vaccines are poised to reduce or nearly eliminate the things we worry most about—severe disease, hospitalization, and death.

Not all our problems are solved. We need to get through the next few months, as we race to vaccinate against more transmissible variants. We need to do more to address equity in the United States—because it is the right thing to do, and because failing to vaccinate the highest-risk people will slow the population impact. We need to make sure that vaccines don’t remain inaccessible to poorer countries. We need to keep up our epidemiological surveillance so that if we do notice something that looks like it may threaten our progress, we can respond swiftly.

And the public behavior of the vaccinated cannot change overnight—even if they are at much lower risk, it’s not reasonable to expect a grocery store to try to verify who’s vaccinated, or to have two classes of people with different rules. For now, it’s courteous and prudent for everyone to obey the same guidelines in many public places. Still, vaccinated people can feel more confident in doing things they may have avoided, just in case—getting a haircut, taking a trip to see a loved one, browsing for nonessential purchases in a store.

But it is time to imagine a better future, not just because it’s drawing nearer but because that’s how we get through what remains and keep our guard up as necessary. It’s also realistic—reflecting the genuine increased safety for the vaccinated.

Public-health agencies should immediately start providing expanded information to vaccinated people so they can make informed decisions about private behavior. This is justified by the encouraging data, and a great way to get the word out on how wonderful these vaccines really are. The delay itself has great human costs, especially for those among the elderly who have been isolated for so long.

Public-health authorities should also be louder and more explicit about the next steps, giving us guidelines for when we can expect easing in rules for public behavior as well. We need the exit strategy spelled out—but with graduated, targeted measures rather than a one-size-fits-all message. We need to let people know that getting a vaccine will almost immediately change their lives for the better, and why, and also when and how increased vaccination will change more than their individual risks and opportunities, and see us out of this pandemic.

We should encourage people to dream about the end of this pandemic by talking about it more, and more concretely: the numbers, hows, and whys. Offering clear guidance on how this will end can help strengthen people’s resolve to endure whatever is necessary for the moment—even if they are still unvaccinated—by building warranted and realistic anticipation of the pandemic’s end.

Hope will get us through this. And one day soon, you’ll be able to hop off the subway on your way to a concert, pick up a newspaper, and find the triumphant headline: “COVID Routed!”