The New Moral Code of America’s Elite

Two students went to Amy Chua for advice. That sin would cost them dearly.

Every striver who ever slipped the rank of their birth to ascend to a higher order has shared the capacity to ingratiate themselves with their betters. What the truly exceptional ones have in common is the ability to connect not only with their superiors but also with their peers and inferiors. And only the rarest talents among them can bond authentically—not just transactionally—with the people who will help them be who they want to be in the world. It’s a preternatural, almost Promethean gift if you have it, and Amy Chua does.

Thus begins the scandal dubbed “dinner-party-gate,” the latest in the annals of Amy Chua, Yale Law’s very own Tiger Mom, whose infamous defense of Supreme Court Justice Brett Kavanaugh was the “dinner-party-gate” of its day approximately three years ago. Then, as now, Chua’s differences with some denizens of her milieu played out in the press, vituperations, allegations, insinuations, and all.

But whatever Chua had done this time, it was either so terrible that it was unspeakable, or so minuscule that it didn’t warrant mentioning in the pages of The New York Times, New York magazine, or The New Yorker. Even so, each outlet gave the mysterious affair a lengthy report. The New York Times declared the conflagration “murky,” something to do with Chua breaking her 2019 agreement with Yale Law School about socializing with students in off-campus settings; The New Yorker noted that the alleged get-togethers had taken place during the pandemic, and considered the rest “a riddle.” Nobody could produce a complainant or a victim; the only thing anyone seemed able to verify was that, whatever Chua had done last winter, the result was that this coming fall, she would no longer be leading a first-year “small group”—intimate cohorts of first-semester law students who are guided through their first few months by a faculty member who teaches, advises, and, per a 2020 budget memorandum from the Law School, likely lunches and dines with the lawyers-to-be.

The reporting left open a pair of related questions: What, exactly, had happened? And, perhaps more salient, if what took place really was something on the order of a minor violation of an ad hoc agreement between Chua and the Yale Law School dean, Heather Gerken, why had the news spilled into the nation’s most prominent news outlets rather than fading below the fold of a campus daily?

It appears to me that what transpired amounts to a skirmish between a notorious professor and an administration that seemed so eager to relieve itself of her presence that it lunged at an opportunity to weaken her position at the expense of two students who were left to deal with the consequences of the ultimately aborted campaign. Still, the answer to the latter question is more revealing than any single aspect of the whole affair. It has to do with the culture of elite institutions, where putatively righteous ends justify an array of troubling means, and noble public virtues like fairness and safety cloak more prosaic motives—the kind of vulgar envy and resentment that people with the best manners deny.

Everyone is just trying to get ahead, after all; this is no less true, and perhaps even more true, at a place like Yale Law School. It just comes more naturally to some than others. In that case one must take matters into one’s own hands.

The proximate drama begins with a trio of second-year law students, friends and acquaintances for a time. There was a person I’ll call the Guest—all three students asked not to be named, and, believing young people should have a chance at carrying on after having their reputation destroyed or destroying the reputation of others, I agreed—who was born and raised in California. He’d arrived at Yale Law School optimistic and younger than most, having come directly from UCLA. During his first semester, he’d befriended the Visitor, a young woman from a suburb of Atlanta, Georgia, who had arrived on campus from Emory. The two made a happy pair: the Guest dreamier and prone to touches of poetry, occasionally drawn to Byzantine history and Christian theology; the Visitor shrewd, practical, and levelheaded, with a keen focus on the concrete facts of policies, problems, current affairs. After working together on a major project that fall, they became and remained close.

And then there was the Archivist, a young man whom the Guest had also befriended early in his time at Yale. The two young men bonded after meeting in their contracts class, after which they would find one another at bars and parties to chat about history, politics, and other shared interests. They met up in New York City for a trip to the Metropolitan Museum of Art; the Guest eventually gave the Archivist a key to his apartment, where the latter would often stop by to visit or do his laundry. In the second semester of their second year, things seemed placid.

And they may have remained that way, had it not been for a minor snag in the Guest’s academic year that put him on a path that would eventually lead him to Amy Chua’s doorstep.

A natural provocateur, Chua has vexed the Law School for years: First with Battle Hymn of the Tiger Mother, a wry ode to the high-pressure parenting tactics of Chinese matriarchs, which didn’t thrill the gently-brought-up sorts who sometimes pass through New England’s finest universities; then with The Triple Package, a book co-authored with her husband, Jed Rubenfeld, on the specific qualities that enable certain cultural groups to succeed in America relative to others—you can imagine how that went over—then with a Wall Street Journal op-ed taking a stand for the embattled Supreme Court nominee Brett Kavanaugh, who, she said, was a “mentor to women,” including her own daughter. All throughout, Chua routinely scandalized the school by making edgy comments (allegedly remarking that Kavanaugh preferred his female clerks on the comely side, for instance, which Chua says is a gross distortion) and, yes, having students over for dinner, serving alcohol, and declining to filter her decidedly piquant inner monologue.

There is another side to Chua. It seems that for every student who emerges from her acquaintance embittered and put off, someone else comes away with nothing but the fondest of feelings for her. Her Twitter feed is peppered with spontaneous congratulations for her accomplished students, and features photos of the professor embracing former protégés in celebration of their success. During this latest contretemps, students advocated in Chua’s favor—quietly, perhaps, but with no less fervor than their anti-Chua counterparts. On April 1, a student emailed a trio of Law School deans: “Professor Chua cares more about her students than any other professor I’ve encountered at YLS. Professor Chua does more to advocate for her students than any other professor I’ve encountered at YLS. Professor Chua does more to mentor her students than any other professor I’ve encountered at YLS,” he insisted. “As you are all likely aware, I am far from the only student who feels this way. Does that not count for anything?” A PDF compilation of student and alumni letters in support of Chua spanned nearly 70 pages of similar sentiments.

Chua’s gift for relationships has also vested her with a great deal of power. Chua does know judges; she does have connections. It’s inconceivable that anyone on staff at Yale doesn’t. But Chua’s roster is either unusually expansive or perceived as such or both, and her status as a legal-career “kingmaker” has cast her in a supercharged penumbra. It’s the sort of mystique that can breed all kinds of resentments, especially in an environment where relationships with people in power are a finite resource.

Then there are Chua’s private, personal relationships—most notably, with her husband, Rubenfeld, a fellow Yale Law professor whose time at the university has been stained of late by allegations of sexual misconduct with students. Per a 23-page brief prepared by Yale Law Women, a respected student advocacy group with a formidable reputation for defending women’s interests on campus, the Rubenfeld saga stretches back to at least 2008, when a poster on the Top Law Schools forum obliquely mentioned rumors of monthly parties at Chua and Rubenfeld’s residence. A decade hence, Dean Gerken hired Jenn Davis, an independent Title IX investigator, to look into a range of allegations concerning Rubenfeld’s behavior with female students, from drunken, unwelcome, off-color remarks to unwanted touching and attempted kissing, on and off school grounds. Rubenfeld has categorically denied the claims. In its report, Yale Law Women said that fear of retaliation by Chua—concern that she would sabotage opportunities for career advancement—discouraged women who resented Rubenfeld’s advances from complaining about them to the administration.

At the conclusion of Davis’s investigation, Rubenfeld was suspended from his duties for two years, a penalty that took effect in 2020. Instead of closing the matter, Rubenfeld’s penalty seemed to strike concerned student groups such as Yale Law Women as a half-measure that would leave the matter to simmer until student turnover and the passage of time permitted another eruption.

Not that the Guest had any reason to contemplate any of this when, early in the spring semester of 2021, he decided to step down as an executive editor at the Yale Law Journal. The Guest, who describes himself as half-Korean, had misgivings about the way the journal’s staff had responded to his questions about the lack of racial diversity in its ranks, and his suggestions for addressing it. Still, even after making his decision, the Guest felt uncertain and unsettled. He confided this to the Visitor, who as a Black student at Yale Law had wrestled with similar questions, and she took it upon herself to bring them up with Chua during a Zoom meeting that served in place of the professor’s usual office hours. At that point, the Visitor recalls, Chua casually offered to talk with the two of them about the Journal affair at her home in New Haven, and the Visitor called the Guest to pass the invitation along.

Unfortunately for the Guest, the Archivist happened to be doing his laundry at his friend’s apartment when the call came, and he overheard the conversation, later documenting it as follows:

Feb. 18. I go over to [the Guest’s] to do my laundry. While at his apartment, I hear him call [the Visitor], who explains to him that Chua has just invited them over for dinner tomorrow. They discuss what to wear and what they should bring (ultimately deciding to bring a bottle of wine). [The Guest] makes zero mention of going over because of any personal crisis. After the phone call, he says that he’s been invited to a dinner party at Chua’s. [The Guest] implores me not to tell anybody so that Chua doesn’t get in trouble.

Despite his gumshoe efforts, the Archivist seemed to come away with a vastly different impression of the meeting than Chua, the Guest, or the Visitor.

The Guest and the Visitor independently told me that the meeting took place sometime in the afternoon, and that Chua offered cheese and crackers, but mentioned that she had dinner plans later on. The Guest recalled that he offered the bottle of wine as a hostess gift, which Chua accepted, though she drank only canned seltzer; the Guest opened the wine, meanwhile, and recalls pouring some for himself.

The Visitor recalled a fairly serious conversation: Chua offered advice about how the Guest should handle the brewing tempest his decision had spawned in their shared teapot. “He was getting press requests,” the Visitor told me. “Should he talk to the press? Professors are like, ‘What happened?’ Should he tell professors? Should he tell anyone? Or should he internalize it? Should he tell judges? Judges are clearly going to know about this, and I’m sure they do. And she wanted to know the full story of what happened. I think a big question was ‘Did I make a mistake?’”

The Guest came away from the conversation feeling reassured. The Archivist, however, was perturbed. Earlier that day, he’d texted two friends that the Guest and the Visitor were “going to dinner” at Chua’s, which, he added, they were “banned by the law school from doing.” One friend replied that this was weird, to which the Archivist replied: “Weird is a nice way to put it!” Chastened, the friend tried again: “So they are still ok with nepotism and complicity as long as it benefits them?” That was the ticket. “Yup!” the Archivist replied. Moments later, the Archivist sent a text that seemed to be more of a press release than a remark: “I think it’s deliberately enabling the secret atmosphere of favoritism, misogyny, and sexual harassment that severely undermines the bravery of the victims of sexual abuse that came forward against Rubenfeld,” he declared. How, why, or whether the Guest or the Visitor actually did any such thing was evidently left to the reader to infer.

Later that night, the Archivist logged a call with the Guest in which, he later said, the Guest sounded “extremely intoxicated”; the Guest denies that he was.

By March, the Journal imbroglio was boiling over into the public sphere. Several of the school’s affinity groups had released statements, and the Journal had released information about the racial makeup of its editors—then the conflict came to the attention of conservative media outlets. Once more, the Guest had a series of questions for someone familiar with bad press.

This time, the Guest and the Visitor brought a premade date-and-cheese plate, the sort of appetizer offering, I gather, that you pick up at Wegmans on the way to Bible study. Again the two of them joined Chua at her New Haven manse for what sounds more like a media-strategizing session than the kind of debauched rager that would eventually possess the imaginations of Chua’s campus detractors. Again, the Archivist recorded the get-together in his notes:

March 13: [The Guest] texts me again at 9:18 PM that he’s outside, indicating he has once again gone to Chua’s but won’t commit to saying so in writing

At that point, it seems, the Archivist had finally had enough. It was time to tell the administration what they had done.

When I was a little girl growing up in suburban North Texas not so very long ago, my grandmother, a housewife of the ’60s, would turn my cousins and me outside to play in the summer so she could sit at her kitchen table and chain-smoke her way through her library of paperback bodice-rippers. And when one of us would inevitably bolt back inside to complain about being annihilated with a Super Soaker at close range or nailed with a Nerf dart to the eye, she would always eject us with the same dismissal: Don’t be a tattletale. As far as childhood admonishments go, it was an interesting one—she wasn’t telling us not to do something, but rather not to be something.

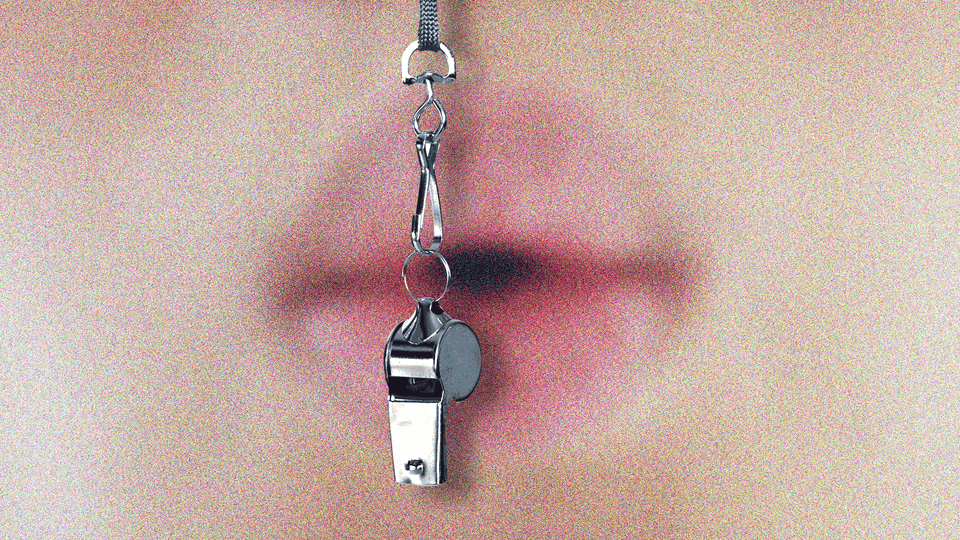

I don’t credit homespun wisdom with any special salience. But the suggestion that it may be useful to morally evaluate oneself before volunteering to monitor everyone else’s conduct isn’t a ridiculous one. It’s wise to be careful that, in one’s zeal for justice or fairness or the more prosaic things that ride beneath those banners, one doesn’t lose sight of one’s own moral obligations or aspirations. And it’s decent, if you have a problem with someone, to take it up with them before running it up the nearest flagpole. But this is something people with the right views and the best degrees, it seems, simply do not do; just as the distinction between tattling and whistleblowing—resting, as it does, on a sober evaluation of one’s own motives and the stakes at hand—is one they often fail to make.

And so on March 22, the Archivist texted a member of Yale Law Women, with the evidence he had gathered proving that the Guest and the Visitor had spent time with Chua at her home. The Yale Law Women member said she would present the goods to Dean of Student Affairs Ellen Cosgrove, who also serves as the Law School’s deputy Title IX coordinator. Per the Archivist’s log, by March 26, the screenshots and notes he had collected thus far were in Cosgrove’s hands.

Up to that point, the Archivist had managed to gather only the flimsiest written evidence that the Guest and the Visitor had been to Chua’s home. Eventually, he composed a roughly 20-page PDF narrating the timeline of his private campaign to turn proof of his friends’ wrongdoing over to the administration—complete with screenshots of text messages, summaries of conversations, a reference to a secretly recorded phone call, and some offhanded musings on his peers’ moral laxity. The document would achieve campus infamy as “the dossier.”

On March 28, two days after the Archivist’s notes first reached Cosgrove, Chua received an email from a reporter at the Yale Daily News at about one in the afternoon. In the email, a reporter explained that the paper had learned that students had complained to Cosgrove about Chua “hosting parties” at her house, which “at least three” students had attended, and that Chua would “no longer be leading a small group” as a result. The reporter speculated that a formal announcement would be made the following day, and requested Chua’s comment.

Chua sent Dean Gerken a stricken one-word email within the hour: “What???” Gerken suggested that they discuss the matter via Zoom that evening, and Chua agreed. Chua told me that during the ensuing confrontation, “after 15 minutes of grilling me about drinking with students and federal judges—and never once mentioning COVID or asking about masks or social distancing—[Gerken] informed me that she had decided ‘to go with a different small-group lineup for the fall.’ She repeated that two more times … Only at that point did I ask whether I could offer to step down [from teaching the small group] rather than be publicly humiliated.”

Gerken responded to The Atlantic’s request for comment and said that the university’s strict confidentiality rules made speaking on the record impossible. In a statement, she added that the law school “does not move to resolve a conflict until both sides have had their say and proceeds in a measured fashion that is consistent with due process.” A spokesperson for Yale Law School told The Atlantic that Gerken’s final “assessment of this situation was based on information Professor Chua shared with her directly, not anonymous text messages among students,” which suggests that the Archivist’s work did not play a decisive role in Chua’s removal from teaching a small group. “Professor Chua has acknowledged that she asked to withdraw from teaching the small group course during a conversation with the Dean,” the statement went on. “When the Dean accepts a faculty member’s offer to withdraw from a course, the matter is closed.” Chua stressed that, contrary to the statement the university gave to The Atlantic, she “absolutely did not withdraw voluntarily.”

On April 7, the Yale Daily News finally reported that Chua had been stripped of the small group she had been set to lead in the fall due to allegations that she had violated the 2019 agreement with Gerken concerning “drinking and socializing with students in all out-of-class settings.” The exposé went on to note that “a student submitted to Law School administrators a written affidavit detailing allegations that Chua hosted law students at her household for dinner on multiple occasions this semester, as well as documented communication between themself and other law school students who acknowledged having gone to Chua’s household.” This served as the equivalent of a book launch for a PDF memoir about spying on your friends, and within a fortnight the dossier was in wide circulation among the student body.

Many of Chua’s colleagues were startled by the news. During an April 21 faculty meeting (which, like so much that happens on campus, was surreptitiously recorded), Gerken informed them that students had come forward with proof—not just statements, she emphasized, but contemporaneous texts and “other evidence”—that Chua had been hosting “parties” where food and alcohol were served, which had caused concern about Chua’s planned small group. Gerken went on to point out that Chua’s denials and her efforts to figure out how and why the get-togethers had come to light added further weight to her apprehensions.

Per comments given to The Atlantic by a spokesperson for Yale Law School, the whole affair was, by that point, long over. Chua had admitted to hosting the Guest and the Visitor, and had agreed to give up the small group. If it really was just a curricular decision between dean and professor, then the twin emails Gerken and Cosgrove sent to the student body on April 9, offering assurance that faculty misconduct has no place at Yale Law School and that any student reporting such would be protected from retaliation, must not have had anything to do with Amy Chua.

But that’s not how the Guest and the Visitor read them. When they had first heard of Chua hosting dinner parties with students during recent months, they had privately wondered who the students in question might be. Now, with the campus awash in rumors about things that had happened before their time, they had no idea what Chua really stood accused of, nor whether or why they seemed to be viewed as aiding and abetting some kind of crime. They sent an anxious, anonymous email to Cosgrove, admitting that they had spent time with Chua in person recently—though, they stressed, “we never met any federal judges. We never met Jed Rubenfeld. There was nothing approaching the level of sexual harassment, verbal or otherwise; bullying; or anything rising to the level of ‘partying.’” But they were upset that neither Yale nor Chua had been forthcoming about the 2019 agreement and, given the recent press reports, questioned the “propriety” of some of Chua’s comments, “considering the power dynamics and setting.” They wanted to know what Chua had done so they could judge to what degree, if any, they had been deceitfully ensnared in her web.

Cosgrove replied to the message from the anonymous email account—first on April 10, then again on the 14th, and once more on the 23rd. But the Guest and the Visitor never wrote back. By then, they had concluded that Chua herself had never been accused of anything like the sexual harassment being discussed on gossip mills like Twitter. They knew she hadn’t been anything but helpful to them. They wanted no part of this.

But it was too late. During the last two weeks of classes, the Guest told me, he was in frequent telephone contact with Cosgrove and her deputy. “They seemed very interested in trying to get me to say something against Professor Chua in a complaint and not in actually helping me in the things that I was very concerned about,” such as responding to the acute invasion of his privacy by a fellow student, he recalled. (A spokesperson for Yale Law School told The Atlantic that Cosgrove objects to this characterization.) Though the Guest had no interest in filing any kind of complaint against Chua, he felt that the administrators tried to persuade him with arguments “framed in terms of ‘Well, you have a moral obligation to protect future generations of students; you need to protect these students; the students think that you need to do this; the students think that you have a moral duty.’” But he demurred. “At one point, I even think I said, like, ‘I don’t know what I’m supposed to complain about. I don’t know what the misconduct is. I don’t know what I’m supposed to complain about.’”

The Visitor remembers feeling subject to the exact same sort of pressure campaign. When the Office of Student Affairs contacted her, she told me, she protested that she felt nothing Chua had done warranted a formal complaint—but she did have significant objections to what the Archivist had done to her and the Guest, distributing their private communications with insulting narration and tarnishing their reputations. (The Archivist told The Atlantic that he did try to keep the Guest and the Visitor anonymous in his communications with the administration—though he had already used their names elsewhere, and his efforts were ineffective, whatever the case.) “[The OSA] would say things like ‘Well, it’s an effort to protect people from Amy Chua, and he’s trying to protect you,’” the Visitor told me. And she still felt they wanted her to file an official complaint. “They said something like, if I remember correctly, ‘All we need you to—all we need is the alcohol, just give us the alcohol. And that’s enough.” (A spokesperson for Yale Law School told The Atlantic that Cosgrove objects to this characterization as well.)

Yale did provide the Guest and the Visitor with information on how to file a complaint against the Archivist and also took additional steps to protect them, including trying to prevent their names from circulating online. But neither the Guest nor the Visitor ever filed any kind of complaint against Chua, who, they still maintain, did nothing worth complaining about. And yet both of them have suffered—not in the jaws of the tigress herself, but in the subtler and more brutal back channels of the Ivy League, where every regal edifice hides a charnel house of human spirits. In the end, they were collateral forfeited in a cold war that began long before they arrived on campus, and that will continue long after it has spit out their bones.

On April 29, the Visitor received an anonymous text message a little after midnight: “Snake.” She replied immediately: “Who is this?” The person replied: “Just know that everyone knows what you did. Trying to bury the Rubenfeld report. Shilling for Chua. And that reputation is gonna follow you.” What had she done? On Twitter, the rumors were more explicit (and just as baseless). “Suddenly I have the urge to deeply thank all my profs who never coerced me into dinner parties which were actually hunting grounds for their sex predator partners,” one user wrote. “Someone made an anonymous complaint that [Chua] was having sex parties with students,” another helpfully explained, “but I don’t see why people can’t just politely disagree.” Another declined to excuse “the sex parties she threw so her husband could fuck college kids.” And again: “The parties help her pimp for her husband’s perversity, part of their own sexual underpinning/agreement. The parties let her abuse her power and get away with it. The parties give her power over students’ career chances.”

And yet, despite so much certainty among students and administrators about Chua’s malign influence over careers, it became clear to the Guest and the Visitor that if they were to actually receive any clerkship or fellowship opportunities at the end of their hellish second year, those achievements would be instantly (and maliciously) attributed to dirty favors done for Chua and Rubenfeld. They began to wonder whether receiving any of the clerkship or fellowship opportunities they had applied for would be worse than losing them.

Maybe it wouldn’t have mattered anyway. On June 10, the Guest received an email from Cosgrove’s deputy, with Cosgrove copied, listing all the measures of kindness and support the administration had offered him during his long ordeal, and assuring him that they had spoken “at length” about his application to serve as a Coker Fellow—a prestigious campus honor—in the coming year and that Cosgrove and her deputy had “encouraged [him] to remain in active consideration for the position.” But when Cosgrove emailed the professor who was considering the Guest for the fellowship a version of the Archivist’s dossier that she had annotated herself, she highlighted “some of the passages that have raised the greatest concern about candor”—the Guest’s, that is. Cosgrove’s highlights include the Archivist’s color commentary, including his opinion of his friend’s willingness to be complicit in misogyny, sexual harassment, and whatever else.

Reached for comment about Cosgrove’s annotation, a spokesperson for Yale Law School said only that “it is routine for the faculty and administration to seek out and share information with each other. Due to confidentiality rules, we are unable to comment further.”

Yale Law School is a funny place: Everyone you talk to says they’re there more or less for charity work, but somehow the graduates keep getting rich and famous. While we all contemplate that mystery, the Guest and the Visitor will be contemplating something very different—how to recover from this strange turn of events. The Guest, whose only documented offense was visiting Chua to talk about his run at the Journal, withdrew his application for the Coker fellowship, and applied for no clerkships. The Visitor quietly accepted one fellowship, and likewise declined to seek any clerkships, reasoning along the same lines as the Guest. What else could they have done? It takes an admirable perceptiveness to know when the truth can’t save you anymore.