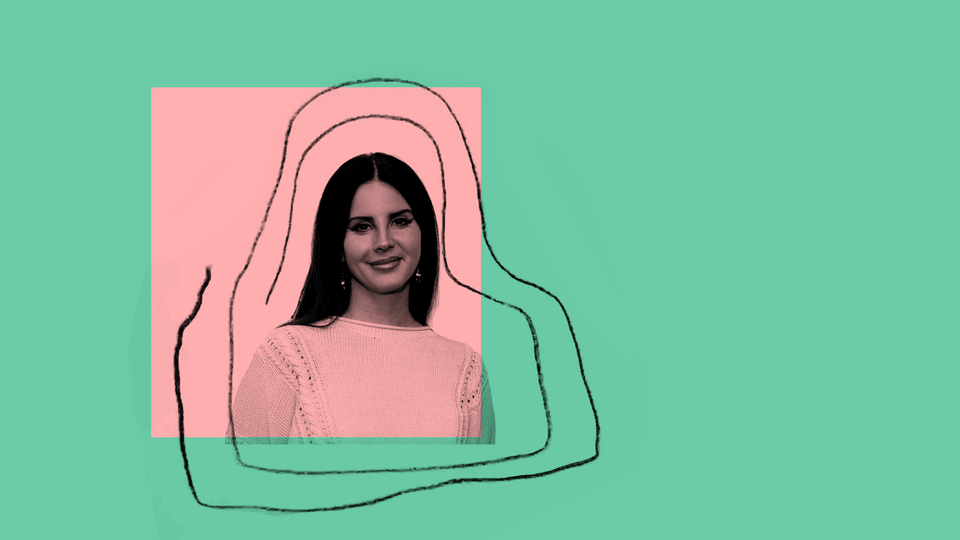

Lana Del Rey Is Still Searching for Happiness

In her new album, big themes—trauma, gender, social collapse—are just details of her inner life.

When the coronavirus pandemic first interrupted life around the world, you likely felt fear for your loved ones and confusion about the future. You might have experienced some less dire pangs too: an urge to stock up on chocolate bars, some relief at not having to commute. Maybe you even had a thought like the one Lana Del Rey shares in her new song “Black Bathing Suit”: “If this is the end / I want a boyfriend.”

Blue Banisters, the eighth studio album by America’s most baffling pop star, swirls with visions of the era we live in. The opener references Black Lives Matter; the closer disses a crypto bro. But 2021 signifiers just dress up Del Rey’s most personal lyrics to date. A decade into fame, she continues to generate both acclaim and controversy, and her latest work clarifies how she does it: by luxuriating in the notion that private desires are, more or less, indifferent to social change. Even when the globe seems to be spinning off its axis, her art suggests that we’re not really living through extraordinary times—or, at least, that some things remain ordinary even when we are.

Del Rey’s disconnect from the current moment is, in a sense, her shtick. Since her 2012 major-label debut album, she’s cooed and pouted in imitations of classic torch singers and folkies, and pastiched tropes about America, femininity, and dysfunctional romance. But musically, she slyly continues to innovate. Her March 2021 album, Chemtrails Over the Country Club, had country flourishes and surprising vocal inflections. Blue Banisters is stranger and, somehow, slower—perhaps reflecting the absence of her recent go-to producer, Jack Antonoff, and his brand of anthemic pop. The songs tend to drift, then thrash, then drift again, as if driven by the thoughts in her head rather than by traditional songwriting rules.

Those thoughts, apparently, revolve around her usual timeless subjects, even as she expresses them in idiosyncratic ways. The blue banisters of the album title are cousins to the white picket fence: The song of the same name, like so many of her others, is about pining for classic domesticity. Over languid piano chords, she sings of a man who promised her bliss, kids, and a newly adjusted weather vane in exchange for some amount of her independence. Del Rey’s narrator presumably refused his offer and now leans on female friends for home-maintenance assistance. On paper this scenario might invite a straightforward girl-power interpretation, but Del Rey’s point isn’t that she doesn’t need a man. She aches, she copes, she aches, she copes—and the song’s gorgeousness lies in that very human tension.

It also lies in verisimilitude. On this album, she’s moving even further from the abstract into the intimate and concrete: Names of real people, places, and pets in Del Rey’s life dot the lyrics, creating the impression that she is documenting her reality rather than, as is often alleged, inhabiting a persona. The effect is not to dispel the clichés of Lana-dom but to deepen them. The chorus of “Black Bathing Suit” sounds like parody—“He said I was bad / Let me show you how bad girls do”—but gains poignancy when one verse references her estrangement from her mom. That subject shows up again on the stunning “Wildflower Wildfire,” when she explains, “My father never stepped in when his wife would rage at me / So I ended up awkward but sweet.”

Glimpses of a scary childhood also add dimension to her yearning for familial stability. Much of Blue Banisters–era Del Rey sounds as morose as ever (“What if someone had asked Picasso not to be sad?” she tuts on “Beautiful”), but she dabbles in Julie Andrews–style sweetness when she trills about her sister on the closer “Sweet Carolina” and when she seems to comfort a child on “Cherry Blossom.” Some of the lovey-dovey moments come close to pure sentimentality—but her sense of humor has a way of keeping them lively. “Fuck you, Kevin,” Del Rey quips to a blockchain stan on “Sweet Carolina.”

If the bitcoin crowd now rallies against her, it will add to the long list of minor scandals that she’s caused over the years. In early 2021, Del Rey hinted that she wanted “revenge” against critics who—to name just a few allegations she has angrily contested—said she defended Donald Trump and disrespected Black women. Blue Banisters hardly plays as a corrective to any public opinions about her. Instead of actually engaging with the social issues she name-drops, she leans into self-involvement. Big themes—trauma, gender, social collapse—are treated as details of her inner life.

“Text Book,” the opener that lurches between spaghetti Western–eeriness and ecstatic reveries, even doubles down on the caricatures people have drawn of her. Think Lana Del Rey celebrates traditional gender relations? Here’s a track about swooning for a guy who drives a Thunderbird like her dad did. When she mentions “screaming Black Lives Matter,” she’s not sending a political message so much as invoking racial-justice protests as sites for a white woman’s self-actualization. Del Rey knows how oblivious or even offensive that will come off to many listeners. But she also knows that some will relate. Her candor about searching for happiness in unhappy times isn’t fashionable—but it’s her edge.