The Dangerous Experiment on Teen Girls

The preponderance of the evidence suggests that social media is causing real damage to adolescents.

Social media gets blamed for many of America’s ills, including the polarization of our politics and the erosion of truth itself. But proving that harms have occurred to all of society is hard. Far easier to show is the damage to a specific class of people: adolescent girls, whose rates of depression, anxiety, and self-injury surged in the early 2010s, as social-media platforms proliferated and expanded. Much more than for boys, adolescence typically heightens girls’ self-consciousness about their changing body and amplifies insecurities about where they fit in their social network. Social media—particularly Instagram, which displaces other forms of interaction among teens, puts the size of their friend group on public display, and subjects their physical appearance to the hard metrics of likes and comment counts—takes the worst parts of middle school and glossy women’s magazines and intensifies them.

One major question, though, is how much proof parents, regulators, and legislators need before intervening to protect vulnerable young people. If Americans do nothing until researchers can show beyond a reasonable doubt that Instagram and its owner, Facebook (which now calls itself Meta), are hurting teen girls, these platforms might never be held accountable and the harm could continue indefinitely. The preponderance of the evidence now available is disturbing enough to warrant action.

Facebook has dominated the social-media world for nearly a decade and a half. Its flagship product supplanted earlier platforms and quickly became ubiquitous in schools and American life more broadly. When it bought its emerging rival Instagram in 2012, Facebook didn’t take a healthy platform and turn it toxic. Mark Zuckerberg’s company actually made few major changes in its first years of owning the photo-sharing app, whose users have always skewed younger and more female. The toxicity comes from the very nature of a platform that girls use to post photographs of themselves and await the public judgments of others.

The available evidence suggests that Facebook’s products have probably harmed millions of girls. If public officials want to make that case, it could go like this:

1. Harm to teens is occurring on a massive scale.

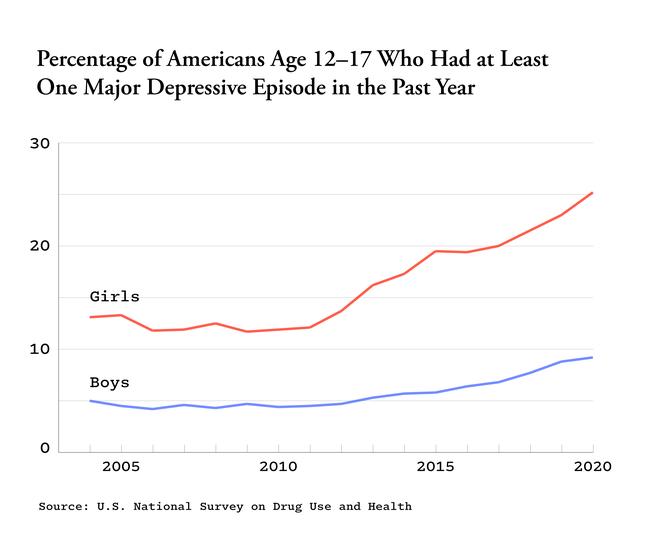

For several years, Jean Twenge, the author of iGen, and I have been collecting the academic research on the relationship between teen mental health and social media. Something terrible has happened to Gen Z, the generation born after 1996. Rates of teen depression and anxiety have gone up and down over time, but it is rare to find an “elbow” in these data sets––a substantial and sustained change occurring within just two or three years. Yet when we look at what happened to American teens in the early 2010s, we see many such turning points, usually sharper for girls. The data for adolescent depression are noteworthy:

Some have argued that these increases reflect nothing more than Gen Z’s increased willingness to disclose their mental-health problems. But researchers have found corresponding increases in measurable behaviors such as suicide (for both sexes), and emergency-department admissions for self-harm (for girls only). From 2010 to 2014, rates of hospital admission for self-harm did not increase at all for women in their early 20s, or for boys or young men, but they doubled for girls ages 10 to 14.

Similar increases occurred at the same time for girls in Canada for mood disorders and for self-harm. Girls in the U.K. also experienced very large increases in anxiety, depression, and self-harm (with much smaller increases for boys).

2. The timing points to social media.

National surveys of American high-school students show that only about 63 percent reported using a “social networking site” on a daily basis back in 2010. But as smartphone ownership increased, access became easier and visits became more frequent. By 2014, 80 percent of high-school students said they used a social-media platform on a daily basis, and 24 percent said that they were online “almost constantly.” Of course, teens had long been texting each other, but from 2010 to 2014, high-school students moved much more of their lives onto social-media platforms. Notably, girls became much heavier users of the new visually oriented platforms, primarily Instagram (which by 2013 had more than 100 million users), followed by Snapchat, Pinterest, and Tumblr.

Boys are glued to their screens as well, but they aren’t using social media as much; they spend far more time playing video games. When a boy steps away from the console, he does not spend the next few hours worrying about what other players are saying about him. Instagram, in contrast, can loom in a girl’s mind even when the app is not open, driving hours of obsessive thought, worry, and shame.

3. The victims point to Instagram.

The evidence is not just circumstantial; we also have eyewitness testimony. In 2017, British researchers asked 1,500 teens to rate how each of the major social-media platforms affected them on certain well-being measures, including anxiety, loneliness, body image, and sleep. Instagram scored as the most harmful, followed by Snapchat and then Facebook. Facebook’s own research, leaked by the whistleblower Frances Haugen, has a similar finding: “Teens blame Instagram for increases in the rate of anxiety and depression … This reaction was unprompted and consistent across all groups.” The researchers also noted that “social comparison is worse” on Instagram than on rival apps. Snapchat’s filters “keep the focus on the face,” whereas Instagram “focuses heavily on the body and lifestyle.” A recent experiment confirmed these observations: Young women were randomly assigned to use Instagram, use Facebook, or play a simple video game for seven minutes. The researchers found that “those who used Instagram, but not Facebook, showed decreased body satisfaction, decreased positive affect, and increased negative affect.”

4. No other suspect is equally plausible.

Many things changed in the early 2010s. Some have suggested that the cause of worsening mental health could be the economic insecurity that followed the 2008 global financial crisis. But why this would hit younger teen girls the hardest is unclear. Besides, the American economy improved steadily in the years after 2011, while teen mental health deteriorated steadily. Some have suggested that the 9/11 attacks, school shootings, or other news events turned young Americans into “generation disaster.” But why, then, do similar trends exist among girls in Canada and the U.K.? Not all countries show obvious increases in mood disorders, perhaps because technological changes interact with cultural variables, but the societies most like ours (including Australia and New Zealand) exhibit much the same patterns.

Correlation does not prove causation, but nobody has yet found an alternative explanation for the massive, sudden, gendered, multinational deterioration of teen mental health during the period in question.

To be sure, there is evidence on the other side. Dozens of studies and several meta-analyses (studies of groups of studies) have examined the relationship between greater digital-media use and worse teen mental health, and most have found just small correlations, or none at all. The most widely cited of these studies, published in 2019, analyzed 355,000 teens across three large data sets from the U.S. and U.K. The authors found only a tiny correlation—no larger than the correlation of bad mental health with self-reports of “eating potatoes.” Facebook cites this research in its defense.

But here’s the problem with these studies: Most lump all screen-based activities together (including those that are harmless, such as watching movies or texting with friends), and most lump boys and girls together. Such studies cannot be used to evaluate the more specific hypothesis that Instagram is harmful to girls. It’s like trying to prove that Saturn has rings when all you have is a dozen blurry photos of the entire night sky.

But as the resolution of the pictures increases, the rings appear. The subset of studies that allow researchers to isolate social media, and Instagram in particular, show a much stronger relationship with poor mental health. The same goes for those that zoom in on girls rather than all teens. Girls who use social media heavily are about two or three times more likely to say that they are depressed than girls who use it lightly or not at all. (For boys, the same is true, but the relationship is smaller.) Most of the experiments that randomly assign people to reduce or give up social media for a week or more show a mental-health benefit, indicating that social media is a cause, not just a correlate.

Facebook would have you believe that merely cutting back the time that teens spend on social media will solve any problems it creates. In a 2019 internal essay, Andrew Bosworth, a longtime company executive, wrote:

While Facebook may not be nicotine I think it is probably like sugar. Sugar is delicious and for most of us there is a special place for it in our lives. But like all things it benefits from moderation.

Bosworth was proposing what medical researchers call a “dose-response relationship.” Sugar, salt, alcohol, and many other substances that are dangerous in large doses are harmless in small ones. This framing also implies that any health problems caused by social media result from the user’s lack of self-control. That’s exactly what Bosworth concluded: “Each of us must take responsibility for ourselves.” The dose-response frame also points to cheap solutions that pose no threat to its business model. The company can simply offer more tools to help Instagram and Facebook users limit their consumption.

But social-media platforms are not like sugar. They don’t just affect the individuals who overindulge. Rather, when teens went from texting their close friends on flip phones in 2010 to posting carefully curated photographs and awaiting comments and likes by 2014, the change rewired everyone’s social life.

Improvements in technology generally help friends connect, but the move onto social-media platforms also made it easier—indeed, almost obligatory––for users to perform for one another.

Public performance is risky. Private conversation is far more playful. A bad joke or poorly chosen word among friends elicits groans, or perhaps a rebuke and a chance to apologize. Getting repeated feedback in a low-stakes environment is one of the main ways that play builds social skills, physical skills, and the ability to properly judge risk. Play also strengthens friendships.

When girls started spending hours each day on Instagram, they lost many of the benefits of play. (Boys lost less, and may even have gained, when they took up multiplayer fantasy games, especially those that put them into teams.) The wrong photo can lead to school-wide or even national infamy, cyberbullying from strangers, and a permanent scarlet letter. Performative social media also puts girls into a trap: Those who choose not to play the game are cut off from their classmates. Instagram and, more recently, TikTok have become wired into the way teens interact, much as the telephone became essential to past generations.

Facebook’s researchers understand the implications of this rewiring. In one slide from an internal presentation on Instagram’s mental-health effects, the presenter notes that “parents can’t understand and don’t know how to help.” The slide explains: “Today’s parents came of age in a time before smartphones and social media, but social media has fundamentally changed the landscape of adolescence.”

Social-media platforms were not initially designed for children, but children have nevertheless been the subject of a gigantic national experiment testing the effects of those platforms. Without a proper control group, we can’t be certain that the experiment has been a catastrophic failure, but it probably has been. Until someone comes up with a more plausible explanation for what has happened to Gen Z girls, the most prudent course of action for regulators, legislators, and parents is to take steps to mitigate the harm. Here are three:

First, Congress should pass legislation compelling Facebook, Instagram, and all other social-media platforms to allow academic researchers access to their data. One such bill is the Platform Transparency and Accountability Act, proposed by the Stanford University researcher Nate Persily.

Second, Congress should toughen the 1998 Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act. An early version of the legislation proposed 16 as the age at which children should legally be allowed to give away their data and their privacy. Unfortunately, e-commerce companies lobbied successfully to have the age of “internet adulthood” set instead at 13. Now, more than two decades later, today’s 13-year-olds are not doing well. Federal law is outdated and inadequate. The age should be raised. More power should be given to parents, less to companies.

Third, while Americans wait for lawmakers to act, parents can work with local schools to establish a norm: Delay entry to Instagram and other social platforms until high school.

Right now, families are trapped. I have heard many parents say that they don’t want their children on Instagram, but they allow them to lie about their age and open accounts because, well, that’s what everyone else has done. Dismantling such traps takes coordinated action, and the principals of local elementary and middle schools are well placed to initiate that coordination.

Haugen’s revelations have brought America to a decision point. If public officials do nothing, the current experiment will keep running—to Facebook’s benefit and teen girls’ detriment. The preponderance of the evidence is damning. Instead of waiting for certainty and letting Facebook off the hook again, we should hold it and other social-media companies accountable. They must change their platforms and their ways.

When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.