China's Long, Bumpy Road to High-Speed Rail

I had previously written about the downfall of the Chinese railway minister Liu Zhijun on corruption charges, concluding then that:

But I doubt Liu's downfall will seriously undermine China's rail plans, since they are larger than the rail ministry. This monumental rail project is viewed as almost nation-building and facilitating the integration of a continental-sized country.

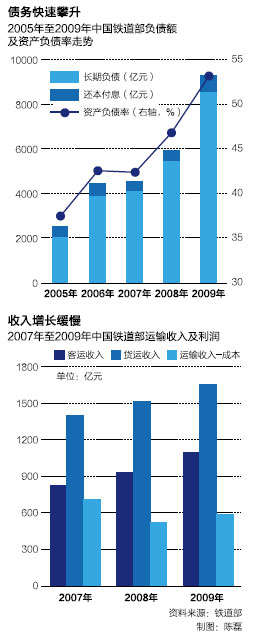

However, the episode will shake the reputation of the rail ministry, and potentially embolden domestic critics of the outsized high-speed rail ambitions. Some have already questioned whether the project is becoming a boondoggle and a drain on resources, even as the Chinese government insists that debt level is about 52%, lower than seen in other countries. So, we'll have to see how this story evolves.

Well, that debate seems to have finally arrived domestically. In what I thought was exceptional original reporting from New Century Weekly (or Caixin), the scion of the "liberal" Chinese press published a fascinating account of high-speed rail (HSR) development (I encourage anyone who reads Chinese to take a look). It is primarily an account of the problems associated with what has been criticized as the "irrational exuberance" of HSR expansion. Granted, these criticisms have popped up sporadically over the last couple of years and are familiar to those who have followed the issue. But the synthesis of the discrete pieces sheds new light on this monumental project. So I think it is worthwhile to summarize the main points/highlights in the piece, since it also provides insight into the process by which China arrived at its HSR pursuit.

1. China did not arrive at its decision on HSR casually or recently. I think intensified coverage in the Western press over the last few years of Chinese high-tech marvels, including sleek new trains, may have created the perception that Beijing performed some impressive sleight-of-hand feats and voila, high-speed trains materialized. In fact, this decision was an iterative and consultative process that began way back in the early 1990s. And it was a process marked often by heated debate over which course China should take. In short, the eventual decision on HSR was far from preordained.

At the time, most experts and policymakers seemed to have agreed on the problem: China needed to expand its rail system because it was over-taxed and needed relief. Coming to agreement on the solution was much harder. Three options were tabled: a) expand regular passenger rail; b) expand regular freight rail; c) expand high-speed passenger rail. Option C was eventually selected, based on what seemed like two considerations. First, as a late-comer to the high-speed game, China should leverage the latest available technology rather than rely on technology of the past. Second, HSR passenger-dedicated lines would free up freight capacity to provide the relief China sought.

But the debate was far from over. The key issue remained whether it made sense to build the Beijing-Shanghai HSR line--stretching some 1,000 kilometers--which was first proposed by an influential state think tank. This pitted two camps, broadly divided into the "pro-rapid expansion" vs. the "pro-gradualism", against each other, with the latter arguing that a line of such length was not economical nor particularly competitive with airlines. A simultaneous debate also emerged over whether that line should be wheel-based trains or maglev (those who've ridden the Shanghai airport express will know that the "maglev" train is wheel-less and basically floats slightly above the track, able to glide along at >450 kilometers/hour). Even then-premier Zhu Rongji supposedly had personal reservations about this project.

2. But then came Liu Zhijun. The now-disgraced railway minister arrived in 2003 at the ministry with out-sized ambitions. Largely accredited as the "father of Chinese HSR," his considerable political skills and the opportunistic seizing of the dark mood during the 2008-09 financial crisis were instrumental in getting his way on the HSR bonanza. This led to what has been likened to the "great leap forward" in HSR construction since 2008--when the world began taking notice.

Indeed, what is happening now in China was crystallized soon after Liu's arrival in 2003, when he commissioned the rail ministry to draft a "Medium to Long Term Rail Network Plan" that aimed for adding 12,000 kilometers of passenger-dedicated rail by 2020. Although the words "high-speed rail" did not specifically appear in that plan, it shrewdly included language that called for trains with speeds above 200 kilometers/hour, which are essentially classified as high speed. Liu seemed to have acquired a keen sense of public sentiment such that if he specifically invoked "H.S.R", it probably would've invited more debate and concern. It was also in that plan that the "four vertical, four horizontal" rail network plan was solidified.

Another important decision was made in 2003. After almost a decade of unsuccessful attempts to indigenously develop a high-speed train, Liu shifted course completely and decided on a "technology transfer for market access" strategy to import foreign technology from the likes of Siemens and Bombardier. That was the only way to build an HSR system fast enough. And the Beijing-Shanghai line was finally to go forward after some 8 years of quarrelsome debate. It broke ground in 2006 and is expected to begin commercial operations later this year.

Then the global financial crisis came crashing down. The gathering storm of the worst economic fallout since the 1930s led to China's behemoth $586-billion stimulus package in late 2008. That proved to be a huge boon for Liu and company, who sprang into action by revising upward the rail expansion goal to 16,000 kilometers. He also undertook a vigorous lobbying effort to receive the largess of a government singularly preoccupied with maintaining jobs and putting a floor on economic contraction. Through whatever political acumen Liu had, he was also able to secure "buy-in" from various provincial governments, strengthening his argument that the rapid execution of this project is good for growth and good for jobs. [In the U.S., Florida turned down stimulus money for an HSR line. Provinces in China generally do not turn down free money.]

Liu got the money. And the great leap forward in HSR construction commenced. That was the decisive defeat for gradualism.

3. Legacy costs, debt, profitability, and safety. Liu's departure left in its wake unanswered questions. Is the Ministry of Railway now weighed down by debt (reportedly at some $260 billion as of 2010, according to the piece)? Most of the debt is supposed to be in the form of long-term bonds. And can the ministry grow out of its debt if/when the new rail lines become profitable? Not sure. As of 2009, freight lines seem more profitable than passenger (in bottom graph, the dark blue bar shows passenger profits and the middle column shows freight). A more sanguine view holds that the debt burden may eventually force the rail ministry to execute substantial reforms, perhaps further commercializing the state enterprises it currently controls so that they operate in more competitive and economically-minded fashion.

Other concerns have crept up, including the fly ash issue that could compromise the integrity of the new tracks as it ages. And some argue that as China continues to push the limits of speed, more maintenance costs will accumulate down the line as new trains' shells will see increased wear and tear traveling at such extraordinary speeds. While much has been made of the affordability of high-speed train tickets for the average Chinese, the piece notes a phenomenon that I wasn't aware of. That is, some train stations apparently have intentionally stopped issuing tickets for regular passenger trains (or claim they've been sold out), forcing ticket sales for high-speed lines. That has led to disgruntled customers vying to get their hands on regular train tickets.

Other concerns have crept up, including the fly ash issue that could compromise the integrity of the new tracks as it ages. And some argue that as China continues to push the limits of speed, more maintenance costs will accumulate down the line as new trains' shells will see increased wear and tear traveling at such extraordinary speeds. While much has been made of the affordability of high-speed train tickets for the average Chinese, the piece notes a phenomenon that I wasn't aware of. That is, some train stations apparently have intentionally stopped issuing tickets for regular passenger trains (or claim they've been sold out), forcing ticket sales for high-speed lines. That has led to disgruntled customers vying to get their hands on regular train tickets.This has been a lengthy dispatch, so I'll just close with a few final thoughts for now. Although the massive rail project was largely a top-down effort that did not enlist the general public, it ostensibly was not a casual and fanciful decision. There was a rationale to it, and it actually took years of vigorous debate, internal consultations, and expert advice before meaningful action was taken. That is emblematic of decision-making in today's China. Seemingly opaque to outside observers, until the final decision is made and suddenly announced, the arrival at a decision actually followed an iterative and probably on balance thoughtful process. Yet how are people to know?

The out-sized victor in this debate also happened to have thrown caution to the wind, and strategically seized opportunities to push for his bureaucratic agenda, in the process probably enriching himself and his network of clients who got favors. Other such examples exist, and occasionally, a big fish gets fried and people get the message.

Coincidentally, the Caixin piece concludes in a similar vein to what I speculated above. It said that those close to the railway ministry do not think the rail plans will be scrapped--too far along for an overhaul. But the recent episode is having something of a ripple effect internally in perhaps rethinking how to approach projects that have yet to break ground or contemplating tweaking the pace of existing projects. Given the stature of Caixin, its coverage will likely trigger more voices to come forward and lend critics some ammunition. Perhaps the "pro-gradualism" camp will even revive its pugilistic spirit.

The rail project was not preordained, and its justification and economic benefit still remain to be seen (for the record, I still think that, on balance, HSR is a good idea for China in and of itself. Execution is another issue altogether). In the meantime, a more open and public debate about this colossal infrastructure project is merited to help determine its future.